PDF: We created a clean, printable PDF of this post for offline reading. Buy it here or view a preview.

In the following, I want to briefly describe an econopathogenic puzzle or riddle that I will then explore and solve in detail.

But before that, it is necessary to make a few brief general theoretical observations:

Modern man has been declining in physical fitness for the past 100 years.

This has been well documented by many prominent sociologists, researchers, and scholars.

And not only is the health and physical fitness of modern man degenerating over time, but the rate of degeneration is progressively accelerating year over year.

This, by any means, should constitute a great cause for alarm, particularly since this is taking place in spite of the high-tech advances that have been made in modern science and medicine along many lines of investigation.

Modern medicine has somewhat eased the sufferings of the masses, but it’s quite difficult to pinpoint a cure it has actually produced since polio.

Indeed, there has been a significant reduction in the epidemic infectious diseases, but modern medicine has not reduced human sufferings as much as it endeavors to make us believe.

Many of the common plagues and diseases of bacterial origin that terrorized our ancestors have decreased significantly due to advances in antibiotics, vaccination, and public health infrastructure, but despite these triumphs of yesteryear, the problem of disease is far from solved.

Alas, there is never absolute victory, there are only tradeoffs.

Today, despite our wins over many bacteria, certain bacterial pathogens still exhibit resurgence and persistence due to antibiotic resistance and epidemiological shifts. Emerging multidrug-resistant strains (e.g., MRSA and MDR-TB), are prime examples of the challenge we face in controlling disease in the context of modern healthcare.

Additionally, the differential persistence of diseases like cholera and tuberculosis underscore the ongoing complexity in achieving comprehensive bacterial disease control.

Modern man is delicate, like a flower; and the present health condition in the United States is in dire straits.

Roughly 22 million healthcare workers attend to the medical needs of 334 million people in the United States. Every year, this population experiences approximately 1 billion illnesses, ranging from minor to severe cases.

In hospitals, over 920,000 beds are available, with roughly 600,000 occupied daily.

Every day, approximately 5% of the U.S. population (about 16.7 million people) is too sick to go to school, work, or engage in their usual activities.

On average, every American—man, woman, and child—experiences around 10 days of health-related incapacity each year.

Children spend an estimated 6-7 days sick in bed per year, while adults over age 65 have an average of around 34 days.

Approximately 133 million Americans (representing 40% of the population) suffer from chronic diseases, including heart disease, arthritis, and diabetes.

Today, around 200,000 people are totally deaf; an additional 500,000 are hearing impaired.

1.6 million Americans are living with the loss of a limb, 300,000 suffer from significant spinal injuries, and 1 million are blind.

Approximately 2 million individuals live with permanent mobility-limiting disabilities.

Approximately 1 in 5 adults in the United States (about 57 million people) experiences mental illness each year, with 5% experiencing severe mental illness that impairs daily functioning; and suicide rates have increased nearly 35% over the past twenty years.

Healthcare spending in the United States is rising, presenting serious challenges for the federal budget, according to projections from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

In 2032, the total health expenditure of the United States is forecasted to reach roughly 7.7 trillion U.S. dollars.

National health expenditures (NHE), which includes both public and private healthcare spending, are expected to rise from $4.8 trillion (or $14,423 per person) in 2023 to $7.7 trillion (or $21,927 per person) by 2032.

Relative to the size of the economy, NHE is projected to grow from 17.6 percent of GDP in 2023 to nearly 20 percent by 2032, as rising healthcare costs will outpace overall economic growth.

Chronic illnesses are estimated to cost the U.S. economy roughly $1.1 trillion per year in direct healthcare costs and around $3.7 trillion in total economic impact when including lost productivity.

Diabetes alone incurs direct costs of $327 billion annually, while cardiovascular disease contributes $219 billion in health expenses and lost productivity.

Medical care, in all its forms, now costs the U.S. economy around $5 trillion per year in direct healthcare costs and lost productivity.

Life expectancy in the U.S. has declined slightly in recent years, influenced by factors like rising chronic disease prevalence, the opioid crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic, with the current national average around 76 years.

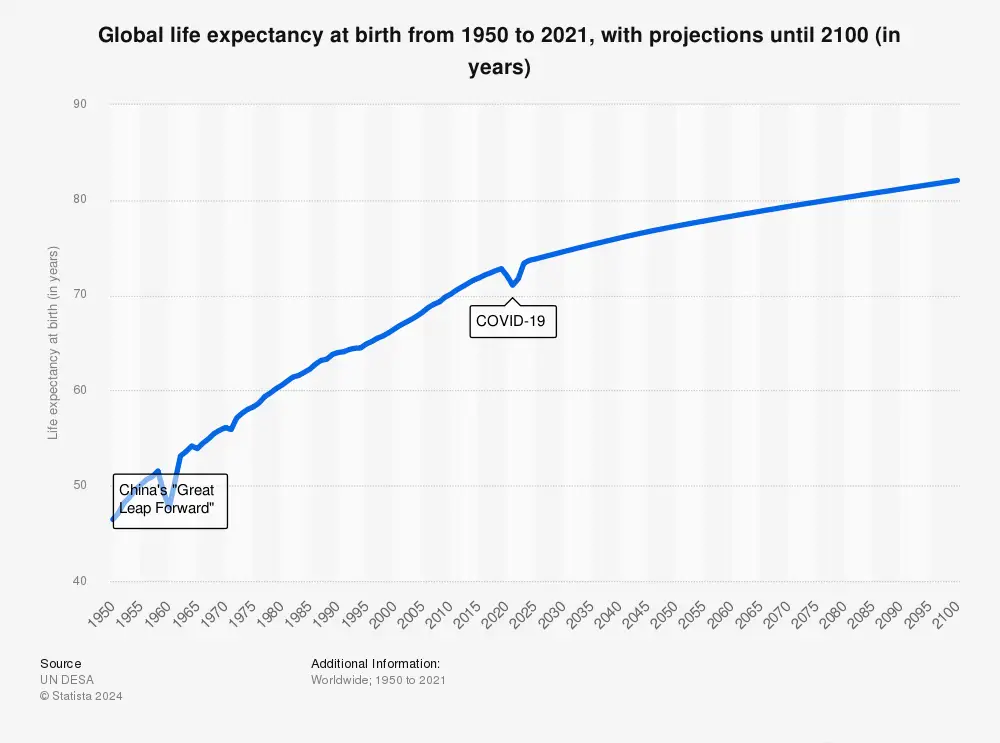

Human longevity is increasing, but chronic disease appears to be increasing along the same axis.

In other words, while we’re extending life, we’re not necessarily extending healthy life.

Despite our increased wealth, knowledge, and scientific capacity, the human organism seems to have become more susceptible to degenerative diseases.

Instead of thriving, more people are spending their later years managing chronic conditions, thereby lowing quality of life and amplifying the financial strain on familial healthcare resources.

So, it would seem that we are merely extending the lifespan of patients living with the new diseases we have created, prolonging their suffering until the disease ultimately kills them.

A note on life expectancy: The American life expectancy of 76 years has a variance of approximately ±15 years, influenced by critical variables including but not limited to lifestyle, genetics, demographics, environmental conditions, psychosocial influences, healthcare access & quality, socioeconomic status, etcetera.

A note on income and disability correlation: Individuals and families living below the poverty line (earning around $15,000 a year for a single person) experience twice the rate of disabling health issues compared to those in higher income brackets. Only one in 250 family heads earning over $50,000 yearly is unable to work due to chronic disability, whereas one in 20 family heads in low-income households faces this barrier. Low-income households experience higher rates of illness, are less likely to consult doctors, and tend to have longer hospital stays than more affluent families. I will discuss the reasons for this later in this text.

Author’s note: In this analysis, I introduce the term ‘econopathogenic’ (from ‘economic’ and ‘pathogenic’) to describe phenomena where economic systems and policies directly and/or indirectly contribute to suboptimal health outcomes. Specifically, I use ‘econopathogenic’ to examine how central banking distortions (e.g., fiat money, fiat science, and fiat foods) have adverse effects on public health through mechanisms affecting the food supply and rates of chronic illness. Although not a formal term in economic or medical literature because I just made it up, ‘econopathogenic’ effectively captures the intersection of economic causation and pathogenic outcomes as explored in this paper.

So, how did we get here?

To paint a full picture, it’s important that we start at the very beginning.

Although the full story stretches back several centuries prior, for the purposes of this paper, we will begin at the turn of the 20th century.

During this time (e.g., the Gilded Age through the Edwardian Era), financial panics were relatively common; and in the United States, the economy was especially volatile and riddled with severe recessions and bank failures every decade.

Now, you may be thinking, ‘But Jamin, they probably only had crazy bank runs and recessions back then because economics and market theory didn’t exist yet,’ and that’s a fair rationalization.

But market theory—as a foundational concept within economics—actually originated thousands of years earlier and was formalized in the 18th century, primarily through the work of Adam Smith.

Author’s note: Some scholars contend that the origins of market theory may date back even further to the development of trade and marketplaces in ancient civilizations. Economics (as a field) began in the 18th century with Adam Smith and became distinct by the 19th century as theories of value, trade, and market behavior were developed even further. As industrialization progressed through the 19th century, economists such as David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus, and John Stuart Mill developed foundational theories on comparative advantage, population growth, and utility. This period marked the establishment of classical economics and later set the stage for neoclassical economics, which emerged toward the end of the century.

That said, I think it is reasonable to assume that by the early 20th century, economists (probably) had a general understanding of what we would consider basic economics today; however, more sophisticated theories on market efficiency—such as Fama’s Efficient Market Hypothesis, Nash’s Game Theory, Monopolistic and Imperfect Competition, Utility Theory, and Bounded Rationality—would not be thought up by other great minds until years later.

It’s also reasonable to assume that the economists and market theorists of that time (probably) had a more limited understanding of competition, pricing, product differentiation, and strategic interaction within markets than the economists and theorists who would emerge 50 to 75 years later.

The experts and great thinkers of the early 20th century lacked both the vast access to information and the theoretical foundation needed to make complex decisions in a stochastic economic environment that we possess today.

To make an already precarious situation even more complex, the U.S. banking system at that time relied heavily on private banks, with no centralized authority capable of setting monetary policy or stabilizing the economy.

Without a central authority to act as overseer, economic conditions were left to the whims of individual banks and a few powerful financiers.

During this time, there was no institution akin to today’s Federal Reserve to intervene in times of crisis by adjusting interest rates or managing the money supply, leaving the nation vulnerable to huge swings in the market.

Jerome Powell wasn’t about to walk through the door with a plan to raise or lower rates in response to economic conditions—no such system existed back then.

This absence of a central regulatory body created a breeding ground for chaos and financial instability, which culminated in the infamous Panic of 1907.

The Panic of 1907 (triggered by a failed attempt to corner the copper market) unleashed a chain reaction of bank runs as depositors scrambled to withdraw their money, fearing the banks would totally collapse.

With no centralized institution to inject liquidity into the economy, private financiers, including the legendary J.P. Morgan, took it upon themselves to stabilize banks and stave off a complete economic breakdown.

This crisis laid bare the urgent need for a centralized framework to manage economic downturns, stabilize liquidity, and prevent future panics.

In the wake of the crisis, policymakers, bankers, and economists convened to study European central banking models, particularly Britain’s Bank of England, which had established effective systems for financial stability.

The Birth of the Fed

In 1913, after extensive deliberation and the theoretical recognition for monetary reform, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law. This legislation established the Federal Reserve System (the Fed as we know it today), America’s first central banking institution, and fiat as we know it was born.

The Fed’s primary task? Stabilize the financial system and manage monetary policy.

Its primary mandates included: providing stability to the financial system by reducing the probability of panics, controlling monetary policy by issuing currency and regulating the money supply, and acting as a lender of last resort by providing liquidity to banks during financial crises.

Essentially, the Fed was designed to:

- Stabilize the financial system: reduce the probability of financial panics.

- Control monetary policy: The Fed could issue currency and adjust the money supply.

- Act as a lender of last resort: The Fed would provide liquidity to banks in crisis.

The Road to Hell: Paved with Good Intentions

The Federal Reserve was initially set up with a decentralized approach, with twelve regional banks across the country overseen by the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C.

This structure allowed the Fed to address local economic conditions while maintaining federal oversight, a unique feature intended to respect the independence of private banks while centralizing monetary policy.

Shortly after the Fed was established, World War I erupted in Europe in 1914. Though initially neutral, the United States became a major supplier of arms and goods to the Allies, which spurred economic growth and increased the demand for a stable financial system capable of handling large international transactions.

By 1917, when the U.S. officially entered the war, the Federal Reserve played a pivotal role in financing the war effort. It issued Liberty Bonds and managed credit and interest rates to stabilize inflation, helping to maintain economic order during a time of unprecedented demand.

The Fed’s success in stabilizing the wartime economy reinforced public confidence in its role, though its capacity was still limited by the gold standard, which required all issued currency to be backed by gold reserves.

During the decade following the end of World War I, the U.S. economy experienced dramatic fluctuations, including a brief post-war recession and a period of rapid economic growth.

However, the seeds of economic collapse were sown years earlier, culminating in the Great Depression of the 1930s, which once again exposed the limitations of the Federal Reserve.

Despite its growing influence, the central bank could not prevent the widespread bank failures and economic devastation that swept across the nation.

The strictures of the gold standard, combined with an inability to coordinate a unified monetary policy response, hampered the Fed’s efforts to mitigate the downturn.

Recognizing these systemic weaknesses, President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented a series of reforms under the Banking Act of 1935 to centralize and strengthen the Federal Reserve’s powers.

The Banking Act of 1935 marked a pivotal transformation for the Fed, centralizing its authority and granting it more tools to manage (and rule) the economy with much greater control.

This Act centralized much of the Fed’s power, granting the Federal Reserve Board enhanced authority over the regional banks and formally authorizing open market operations as a core tool for managing the money supply.

The Act’s provisions enabled the Fed to more effectively influence credit conditions, interest rates, and liquidity, establishing it as a central pillar in economic governance.

These newly centralized powers positioned the Fed to intervene more decisively, allowing it to play a critical role in economic stabilization and respond dynamically to national and global challenges.

As the 1930s drew to a close, and with the memory of the Great Depression still raw, the United States faced mounting global tensions and economic pressures. The Great Depression had devastated economies worldwide, leading to political instability, rising nationalism, and economic self-interest.

Meanwhile, the European political landscape deteriorated as fascist and totalitarian regimes in Germany, Italy, and Japan aggressively expanded their territories, threatening global peace and challenging U.S. interests abroad.

Although initially isolationist, the U.S. found it increasingly difficult to remain detached from global affairs as Axis powers gained influence.

Economically, the U.S. began supporting Allied powers even before formally entering the war. Programs like the Lend-Lease Act allowed the U.S. to provide arms, resources, and financial support to Allied nations, bolstering their capacity to resist Axis advances.

However, this support required substantial financial resources, drawing heavily on the Fed’s enhanced ability to influence monetary conditions.

Author’s note: The Great Depression lasted from 1929 to 1939. It began with the stock market crash in October 1929 and persisted through the 1930s, with varying degrees of severity, until the economic recovery associated with the onset of World War II.

Fiat Currency: The Backbone of Total & Sustained War

When the U.S. finally entered World War II in December 1941 (following the attack on Pearl Harbor) the need for large-scale financing to support the war effort became even more clear than ever. The Fed’s powers, strengthened by the 1935 reforms, enabled it to manage wartime borrowing by keeping interest rates low and controlling inflation.

By stabilizing the financial environment, the Fed facilitated the issuance of War Bonds and other government securities, which financed military production, troop mobilization, and other war-related expenses. The Fed’s ability to conduct open market operations allowed it to influence the money supply directly, ensuring that credit remained affordable and available for both the government and private sectors essential to wartime production.

Under this new money system, the U.S. government could, with the Fed’s support, expand the money supply to finance massive expenditures without immediately depleting its gold reserves.

Although the U.S. was still technically on the gold standard during WWII, the Fed’s expanded powers allowed for a quasi-fiat approach, in which the money supply could be adjusted flexibly to meet the needs of the war effort.

This set a precedent for using monetary policy as a tool for national objectives, a practice that would become more pronounced in the postwar era.

Author’s Note: The sustained and perpetual nature of modern warfare is a direct result of the economic structures and monetary policies that finance it. Easy money, for example, a byproduct of our fiat system, provides a tremendous incentive for perpetual war, sustaining wartime industries dependent on government contracts. This echoes Dwight D. Eisenhower’s concern that the military industries that prospered in WWII evolved into a “Military Industrial Complex” that drives U.S. foreign policy toward endless, repetitive, and expensive conflicts with no rational end goal or clear objective.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the U.S. has not raised taxes to pay for the Iraq War, the War in Afghanistan, its recent foray into Syria, or its latest proxy war with Russia, despite spending trillions of dollars. With a national debt of $36 trillion—and no intention of ever tying military spending to increased taxation—all this spending on sustained and perpetual war is just a ‘deficit without tears’. This approach enables the United States to maintain global military engagements—such as deploying forces to scores of nations and engaging in sustained conflicts over long timescales—without significant public backlash.

Any reasonable person would assume that people prefer peace to war. Furthermore, while a nation’s people may support government spending on future-oriented investments like infrastructure and preventative healthcare, they are unlikely to support bloody military campaigns in distant lands. Thus, because people prefer peace to war and are aware of how their government spends public funds (aka their money), a government that spends (and overspends) on perpetual and sustained war risks being overthrown.

In Adam Smith’s seminal work, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), he arrived at similar conclusions:

“Were the expense of war to be defrayed always by a revenue raised within the year, the taxes from which that extraordinary revenue was drawn would last no longer than the war… Wars would in general be more speedily concluded, and less wantonly undertaken. The people feeling, during the continuance of the war, the complete burden of it, would soon grow weary of it, and government, in order to humor them, would not be under the necessity of carrying it on longer than it was necessary to do so.”

In 2016 alone, the United States had a military presence in over to 80% of the world’s nations and dropped over 26,000 bombs in seven different countries—an average of three bombs per hour, 24 hours a day, for the entire year. Barack Obama, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, became the first U.S. president to preside over American war every single day of his presidency.

Back to Back World War Champions

By the time World War II neared its end, the global economy was in disarray. The devastation across Europe and Asia, combined with the massive debts accumulated by nations involved in the war, had left the world in urgent need of financial stability and a reliable framework for reconstruction.

The United States, on the other hand, emerged from WWII with the strongest economy and the largest gold reserves, holding around 20,000 tons of gold, nearly three-quarters of the global supply.

This was a significantly stronger economic position than most other countries, giving the U.S. an unparalleled degree of leverage in shaping the world economy at the time.

Asserting its newfound powers, the U.S. sought to leverage this position to establish a new economic order that would both secure its dominance and promote global stability.

USD Becomes the Most Dangerous Weapon Ever Made

In July 1944, with another World War Championship victory on the horizon, 730 delegates from 44 Allied nations convened at the Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, for a historic (and little talked about) conference that would shape international finance for years to come.

This meeting would come to be known as the Bretton Woods Conference, and the resulting agreements would lay the foundation for the postwar financial system and a new international financial order.

The primary objectives of the conference were:

- To rebuild war-torn economies.

- To promote economic stability.

- To stabilize exchange rates.

- To prevent the economic instability that had contributed to WWII.

- To promote international economic cooperation and prevent future wars.

At the heart of the Bretton Woods system was the creation of a new global monetary framework that would reduce the risk of currency volatility and facilitate international trade.

Notably, the key players and nations at the table were instrumental in shaping the global economic order and establishing a balance of power that would define the postwar era—an order that continues to this day.

The main architects of the Bretton Woods system were British economist John Maynard Keynes and the U.S. Treasury representative Harry Dexter White.

Keynes was one of the most influential economists of the time (and perhaps of all time) and had developed innovative theories on government spending and economic intervention. We will discuss Keynesian theory later in this text.

White, meanwhile, was a powerful figure in the U.S. Treasury with an agenda that aligned with America’s strategic interests.

While most nations were represented at the conference, it was not an equal playing field.

At the conference, the U.S. insisted on making the dollar central to the global financial system, even though Keynes had created a proposal for a new international currency, named the “bancor,” that would prevent any single country from gaining excessive power.

While most other countries initially favored Keynes’s proposal, White and the American delegation strongly opposed this idea, advocating instead for a system based on the U.S. dollar.

The underlying message was clear: the U.S. would use its economic leverage to shape the world’s financial architecture to its advantage.

It’s worth noting, the U.S. held significant sway over the proceedings because it was the world’s economic superpower at the time, with a large trade surplus and around two-thirds of the world’s gold reserves. This gave the World War I and II Champs substantial leverage in shaping the outcome of the conference to suit its own interests.

This dominance allowed the U.S. to dictate many terms, leading some historians to argue that Bretton Woods was an exercise in American “dollar diplomacy“—a strategy that pressured other nations into adopting a dollar-centric system.

While not overt bullying in a political sense, the U.S. leveraged the weakness and indebtedness of its allies to secure their cooperation. Since war-torn nations like the United Kingdom needed American support for reconstruction, they had little choice but to accept the new financial order.

As such, the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 was driven largely by the United States, and it established the U.S. dollar as the world’s reserve currency, cementing American economic and military dominance for decades to come.

The agreement established two major institutions:

- The International Monetary Fund (IMF): Now part of the World Bank, these guys were charged with overseeing exchange rates and providing short-term financial assistance to countries experiencing balance-of-payments issues.

- The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), later part of the World Bank, which was focused on long-term reconstruction and development loans to war-ravaged economies.

Note: In addition to the primary institutions listed above, several others were created or directly influenced by Bretton Woods principles:

- United Nations (UN) (1945) – Established shortly after Bretton Woods, the UN was created to promote international cooperation and peace, with agencies like UNESCO and UNICEF in support.

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (1947) – Created to reduce trade barriers, later evolving into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (1961) – Originally established as the Organization for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) in 1948 to administer the Marshall Plan, it later evolved into the OECD, focusing on economic cooperation and policy coordination among its member nations.

The core principle of the Bretton Woods system was a system of fixed exchange rates pegged to the U.S. dollar, which itself was convertible to gold at $35 an ounce. This effectively made the U.S. dollar the world’s reserve currency, as other currencies were indirectly tied to gold through their dollar pegs.

By pegging the dollar to gold at $35 per ounce and tying other currencies to the dollar, the U.S. gained unprecedented control over global finance, enabling it to print money with global backing.

This financial leverage not only funded America’s immediate war efforts but also allowed it to build the largest and most advanced military infrastructure in history, positioning the U.S. as a global superpower.

The Federal Reserve’s role in this system was significant, as it cemented the dollar’s central role in global finance and positioned the Fed as a key player in the international monetary landscape. By facilitating stable exchange rates, the Bretton Woods system aimed to prevent the economic disruptions that had destabilized prewar economies.

This arrangement provided the U.S. with substantial financial leverage, allowing it to project economic power globally while reinforcing its domestic economy through the demand for dollars.

The Bretton Woods system effectively required nations to maintain large reserves of U.S. dollars, which created a steady demand for American currency. As foreign central banks accumulated dollars, they were also entitled to redeem those dollars for gold, at the rate of $35 per ounce, with the Federal Reserve.

With a steady international demand for fiat USD (especially during times of instability or economic uncertainty) the U.S. could run deficits without the immediate risk of currency devaluation, thereby fueling robust economic growth at home.

The Bretton Woods system was stable, and promoted foreign investment in the U.S. economy, which helped solidify America’s dominance we see today; it also provided the resources needed to develop military capabilities unmatched by any other nation in the history of the world.

Through this financial system, the U.S. created an economic and military juggernaut that shaped the postwar world order, leaving it at the helm of both global security and finance.

The Expansionary “Gold Drain”

After WWII, the U.S. economy entered a period of unprecedented expansion, with strong consumer spending, industrial growth, and government investment.

This expansion, however, soon led to challenges within the Bretton Woods system.

The Fed adjusted its policies to manage inflation and stabilize this growth, influencing interest rates to maintain low unemployment while avoiding economic overheating.

And, in the beginning, Bretton Woods was able to strengthen U.S. economic dominance and allowed it to run trade deficits without immediate consequences, but as the 1960s progressed, the system became increasingly problematic.

As European and Asian economies recovered and grew, they began to redeem their dollar reserves for gold, leading to a “gold drain” from U.S. reserves.

The gold drain accelerated as more and more foreign countries, particularly France, began exchanging their dollars for gold. French President Charles de Gaulle was particularly vocal in criticizing the U.S. for abusing its “exorbitant privilege” of printing the world’s reserve currency.

This situation reached a critical point by the 1970s, as the volume of dollars held abroad began to exceed the gold held by the U.S. government.

These mounting economic pressures, compounded by the costs of the Vietnam War and rising inflation, made maintaining the dollar’s gold convertibility unsustainable.

So, in 1971, President Richard Nixon made the decision to “close the gold window”–effectively taking us off the gold standard, a move known as the “Nixon Shock.”

This effectively ended the Bretton Woods system and shifted the U.S. to a 100% fiat currency system.

By shifting to a fully fiat currency system, the U.S. retained control over its currency, giving the Federal Reserve greater latitude in managing monetary policy. Other countries gradually followed suit, allowing their currencies to float freely against the dollar.

The transition marked the beginning of a new era in global finance, with floating exchange rates and the dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency. This system continued to ensure U.S. dominance in global finance, with the dollar remaining central to international trade and investment.

Freed from the constraints of the gold standard, the Fed gained greater flexibility (and more power) to manage the economy, allowing it to adjust interest rates and money supply more freely to combat inflation and address domestic economic challenges.

Other nations gradually followed suit, allowing their currencies to float against the dollar, which cemented the dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency.

We are now officially living in a fiat world.

For the uninitiated, fiat is: a government-issued currency that’s not backed by a physical commodity such as gold or silver; nor by any other tangible asset or commodity.

Fiat currency is typically designated (and backed) by the issuing government to be legal tender and is authorized by government regulation.

Fiat currency is money that has no intrinsic value (it isn’t backed by anything) instead, its value comes from government decree and public trust in its stability and purchasing power.

It has value only because the individuals who use it as a unit of account–or, in the case of currency, a medium of exchange – agree on its value.

In other words, people trust that it will be accepted by merchants and other people as a means of payment for liabilities.

The U.S. dollar, as discussed above, became a purely fiat currency in 1971 when President Nixon ended the dollar’s convertibility to gold, decoupling the dollar from gold and ending the Bretton Woods system.

This move allowed the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government control over the money supply, enabling them to rule with an iron fist and create money “out of thin air” without needing to hold physical reserves.

In our fiat system, The Fed can expand money to achieve certain economic goals, and can control the supply of money through monetary policy tools (e.g., adjusting interest rates, buying or selling government securities, and setting reserve requirements for banks, etc.).

While there are some benefits to having “The Fed”, one of the significant suboptimalities is that it creates inflation.

I know there has been a lot of confusion on this topic in American political and social circles in recent years, but inflation is caused by one primary mechanism and can be compounded by several other sub-mechanisms.

Before we get to the fancy stuff, however, we must first define what inflation means.

Inflation, in simple terms, is the decline in purchasing power of a currency, or the devaluation of that currency, which generally shows up as rising prices for goods and services.

Here’s how inflation is created in a fiat system:

The primary mechanism that causes inflation is money supply expansion (most notably without a corresponding increase in the production of goods and services).

When The Fed prints money and/or injects funds into the economy (e.g., stimulus payments, funding wars, quantitative easing, etc.), more dollars are circulating. If the supply of goods and services doesn’t increase at the same pace, the result is “too much money chasing too few goods,” and prices go up as people compete to buy the same amount of goods with more money.

Inflation can occur in several ways:

- The Fed expands the money supply by:

- Lowering interest rates (which encourages borrowing and spending).

- Conducting open-market operations (buying government securities).

- Engaging in quantitative easing, where they buy a broader range of assets, further increasing liquidity.

- Government spending & debt: When governments finance spending by borrowing heavily or creating money, they increase the money supply. This is especially true if the central bank funds government debt by buying bonds, essentially monetizing the debt and creating new money. Some examples include: (wars, infrastructure, interest on national debt, stimulus packages, federal assistance, subsidies, etc.).

- Credit Expansion: When banks increase lending (see point #1) they effectively create more money in the form of credit. This additional purchasing power drives up demand in the economy, which can lead to higher prices if supply doesn’t keep pace.

- Policy Choices in Times of Crisis: In economic crises, the government and central bank may flood the economy with liquidity to prevent collapse, as seen during the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. While these measures may stabilize the economy short-term, they expand the money supply significantly, risking inflationary pressures later.

- Supply Shocks: While not strictly an increase in the money supply, a supply shock (e.g., oil shortages or disruptions in global supply chains) can cause inflation by reducing the supply of goods, creating upward pressure on prices. This type of inflation (cost-push inflation) is more temporary but can lead to higher inflation expectations if prolonged.

Author’s note: When government spending is financed by debt, as is the case here in America, The Fed may buy government bonds, essentially “printing money” to support that debt. This increases the money supply, often leading to demand-pull inflation, as more dollars are chasing the same amount of goods and services. So, while government spending can be beneficial in various ways, it will always contribute to inflationary pressure when growth in government outlays exceeds economic productivity or when it requires ongoing debt financing. The combination of high demand, low supply, and expanded money supply will push prices upward, resulting in a classic case of nasty inflation.

Inflation: Destroyer of Worlds

Inflation can be a tricky and often difficult concept to wrap your mind around, especially when you are just starting out as an economic theorist (or what I like to call, an econ yellow belt).

At Clemson, I had an economics professor who simplified the concept of inflation (and how it can wipe out a society) using two historical examples.

The first example is the story of the ancient monetary system based on Rai stones on Yap Island, and the second is the fall of Rome.

First, we will discuss Yap Island.

One of the most interesting case studies of money I have ever studied is the primitive money system of Rai stones on Yap Island, located in present-day Micronesia in the Western Pacific.

What is a rai stone?

A Rai stone is a large, disk-shaped piece of limestone that was formerly used as currency on the Micronesian island of Yap. These stones, ranging in size from a few inches to several feet in diameter, are characterized by a hole in the center, which allowed them to be transported using wooden poles. Despite their massive size and weight—some rai stones can weigh several tons—they served as a sophisticated and abstract form of money.

These massive stones served as a form of currency not for daily transactions but for significant social and ceremonial exchanges.

Their story, however, also illustrates how an external force—inflation driven by human action—can disrupt a carefully balanced economic system, leading to one of the earliest examples of inflation driven by overproduction of a currency.

Rai stones were quarried from Palau, hundreds of miles away, and transported back to Yap in perilous voyages. Their value depended not just on size but also on factors like craftsmanship, historical significance, and the degree of difficulty of transportation.

Ownership was socially acknowledged rather than requiring physical possession; a stone could remain in place while its “owner” used it as payment by transferring title through communal agreement.

This system worked because it was underpinned by trust and scarcity. The difficulty of quarrying and transporting rai stones kept their numbers limited, and each stone’s history added to its cultural value. Even stones lost at sea could retain value, as long as the community remembered the story of their loss.

Author’s note: The exact date when Rai stones were first used on Yap Island is not precisely known, but it is generally believed that their use as a form of money began around 500-800 CE, possibly earlier. Archaeological and historical research suggests that the Yapese started quarrying limestone from Palau during this period, indicating the early origins of the rai stone system.

In the late 19th century, an Irish-American sea captain named David O’Keefe, stumbled upon Yap after being shipwrecked. Observing the Yapese reliance on Rai stones, he saw an opportunity to make a quick buck by leveraging his access to modern tools and ships. O’Keefe began trading iron tools and other Western goods with the Yapese in exchange for their labor to quarry Rai stones more efficiently.

Using modern technology and his ships, O’Keefe was able to transport a much greater quantity of Rai stones from Palau to Yap than had ever been possible using traditional methods.

Previously, the difficulty and danger of acquiring rai stones had maintained their scarcity and high value. O’Keefe’s operations drastically reduced the labor and risk involved, and he was able to flood the Yapese economy with new stones.

The injection of new Rai stones into the Rai stone “money supply” destabilized the local economy, undermining their scarcity and value in what would come to be known as one of the first massive economic collapses of the ancient world.

By increasing the quantity of stones available, O’Keefe had undermined their scarcity, which was central to their value. As the supply expanded, the relative worth of individual stones diminished. This inflation eroded the traditional monetary system, as people began to lose confidence in the stones’ ability to function as a reliable store of value.

In the end, the Yapese became increasingly reliant on O’Keefe’s Western goods, further integrating their economy into a globalized trade network. Over time, the Rai stones’ role as functional money decreased and the stones became worthless, relegated instead to ceremonial and symbolic uses.

This story serves as a timeless reminder of an enduring economic rule: when the supply of money exceeds demand, its purchasing power inevitably declines—a principle that remains evident in our modern currency systems today.

The Collapse of Rome

The Roman Empire’s collapse, on the other hand, driven by systemic inflation and currency debasement, presents a paradigmatic case study in fiscal deterioration.

In the beginning of this self-destructive journey, Rome had a robust monetary framework, grounded in the silver denarius and gold aureus, each backed by tangible metal content and widely trusted as reliable stores of value across every corner of the Empire.

The denarius, with 3.9 grams of silver, was first introduced around 211 BCE during the Roman Republic, as a standardized silver coin to support trade and serve as a reliable everyday currency.

The aureus followed much later, standardized by Julius Caesar around 46 BCE as a high-value gold coin intended for substantial transactions, especially for military and international trade; and as a store of wealth.

Together, the denarius and aureus allowed Rome to manage a robust economy, with the denarius used for daily exchanges and the aureus reserved for larger, higher-value transactions.

The aureus, with 8 grams of gold, standardized transactions and cemented economic interconnectivity across the Mediterranean.

Rome enjoyed economic stability, despite political turmoil, until the reign of Nero (54–68 AD), when practices like coin clipping and debasement began to undermine the currency’s value.

Nero was the first emperor to engage in “coin clipping,” a practice whereby the state—and sometimes even common plebs—would shave small amounts of metal from the edges of coins, keeping the clippings to melt down into new coins.

These clipped coins circulated at full face value but were visibly smaller over time, eroding public confidence and contributing to inflation.

To make things worse, Nero also introduced the concept of debasement, a state-led process of melting down coins and mixing cheaper metals (fillers) such as copper, into the silver.

These debased coins contained less silver, allowing the government to mint more coins from the same amount of precious metal (and finance the Empire’s ballooning expenditures) thereby funding military campaigns and public projects without having to raise taxes.

I’m sure at some point the Roman government was celebrating all their success and marveling at their genius.

“How come nobody has thought of this before!” “Getting rich is so easy!” they may have thought to themselves.

Little did they know that this money hack did nothing but increase the money supply at the cost of each coin’s intrinsic value, creating the first well-documented instance of government created, empire destroying inflation.

The reduction of silver content from 3.9 grams to 3.4 grams, though initially modest, catalyzed a systemic shift toward perpetual debasement as Nero’s example became a template for successive emperors to fund escalating military and administrative costs without imposing unpopular tax hikes.

This set a precedent for successive emperors, who perpetuated and intensified debasement to fund escalating military campaigns and administrative costs.

The resulting (and inevitable) inflation eroded public confidence in the currency, diminished its purchasing power, and led to widespread hoarding of gold, further exacerbating monetary contraction.

The cumulative effect was a destabilization of the Roman economy: trade diminished as currency value fluctuated unpredictably, tax revenues declined, and socioeconomic stratification intensified as wealth consolidated in landownership rather than fluid capital.

These economic maladies, intertwined with political fragmentation and external pressures from incursions by non-Roman entities, culminated in the disintegration of centralized imperial authority.

In the discourse of economic historiography, the Roman Empire serves as a paradigmatic example of how fiscal and monetary policies can precipitate systemic decline.

It’s quite arguably the single most important historical lesson on the critical correlation between monetary integrity and state stability, demonstrating that protracted fiscal imprudence and inflationary policies can undermine even the greatest of empires.

Rome was (probably) the greatest empire to exist in the ancient world, but in the end, coin clipping and debasement gradually eroded the purchasing power of Roman currency, creating an inflation so significant it eventually destabilized the economy and led to the eventual destruction of the Empire.

Could the same thing happen here in America?

History often repeats itself, but in such cunning disguise that we never detect the similarities until it’s too late.

There are parallels we can draw between the debasement of the Roman coinage and the debasement of modern fiat currencies.

The United States appears to be following a trajectory similar to that of ancient Rome.

Only our techno-accelerated path is going a thousand times faster.

Where along the curve are we?

Are we at the beginning, the middle or the end?

What are the choices going to be for us?

What’s the end game?

Will we go down with civil war, foreign invasion and economic chaos and into a long period of civilizational decline, like the Romans?

Or will it be more like the recent British Empire example, where financial and military power recedes and yet the nation still remains a significant player in the world (although dethroned as the top dog)?

And if you think the way of Rome can’t happen here in the states, let’s take a quick look at the dollar’s buying power over time.

Let’s rewind back to 1913, where our story began.

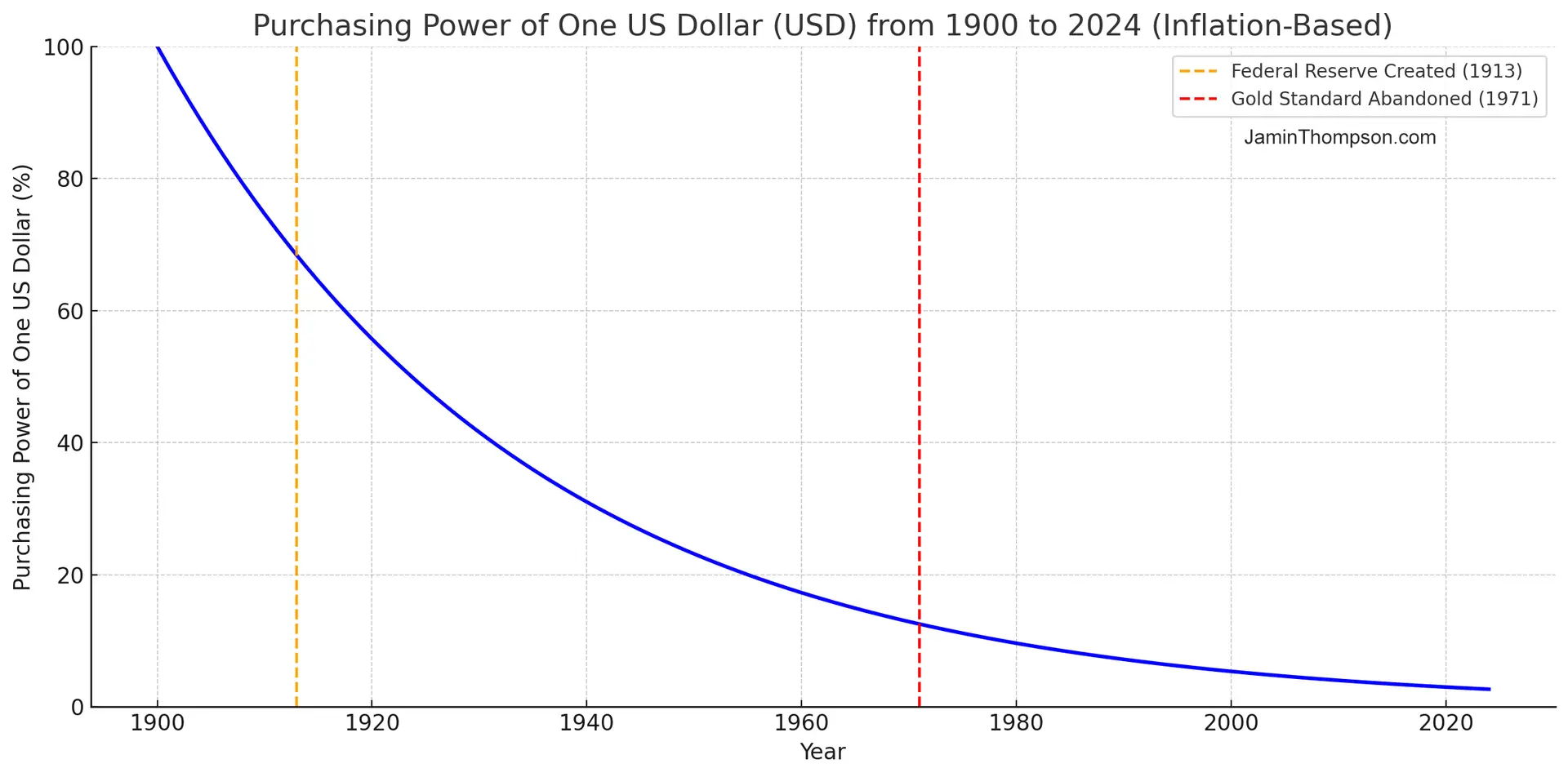

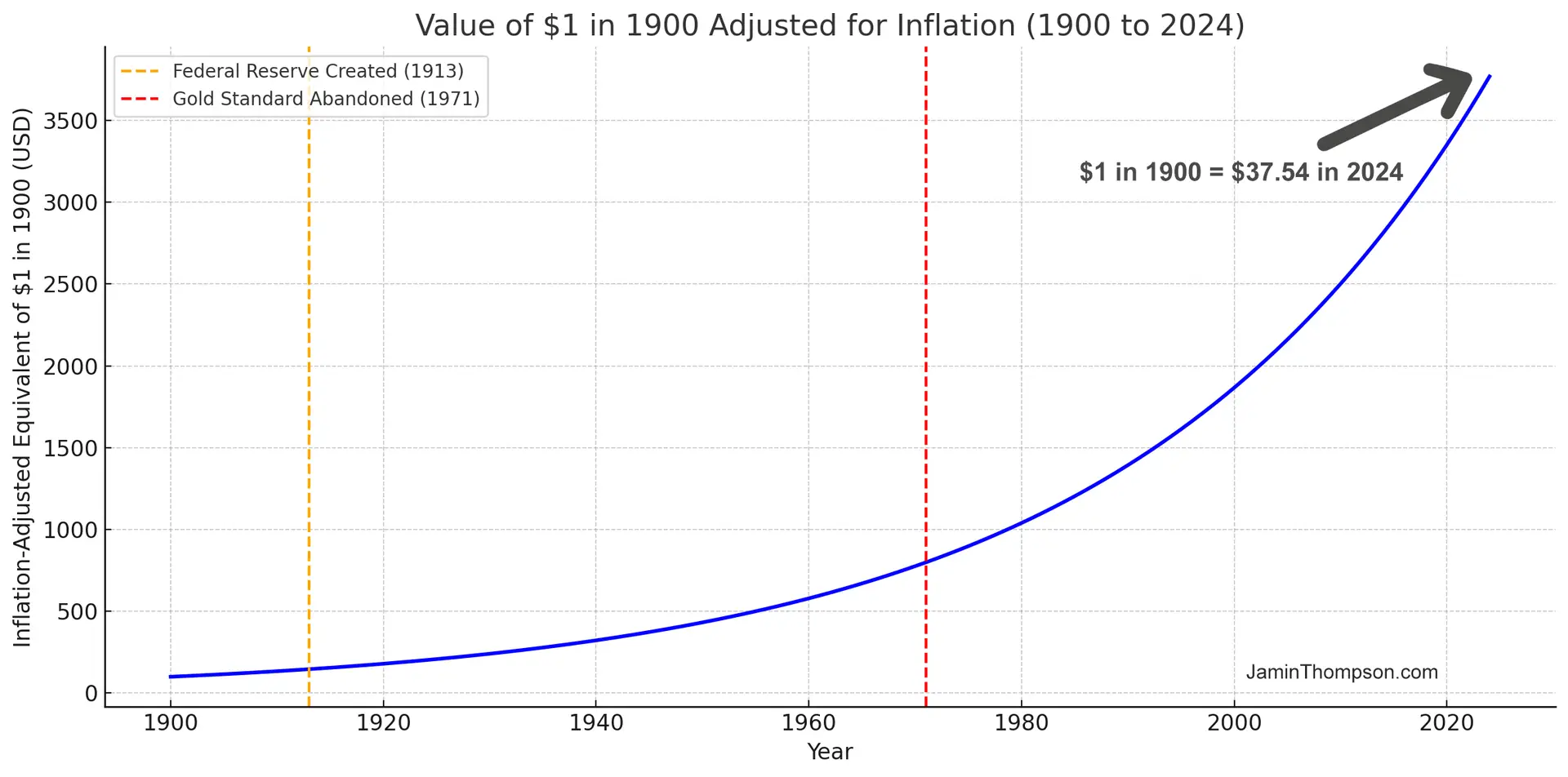

If you purchased an item for $100 in 1913, then today in 2024, that same item would cost $3,184.86.

In other words, $100 in 1913 is worth $3,184.86 in 2024.

That’s a 3084.9% cumulative rate of inflation.

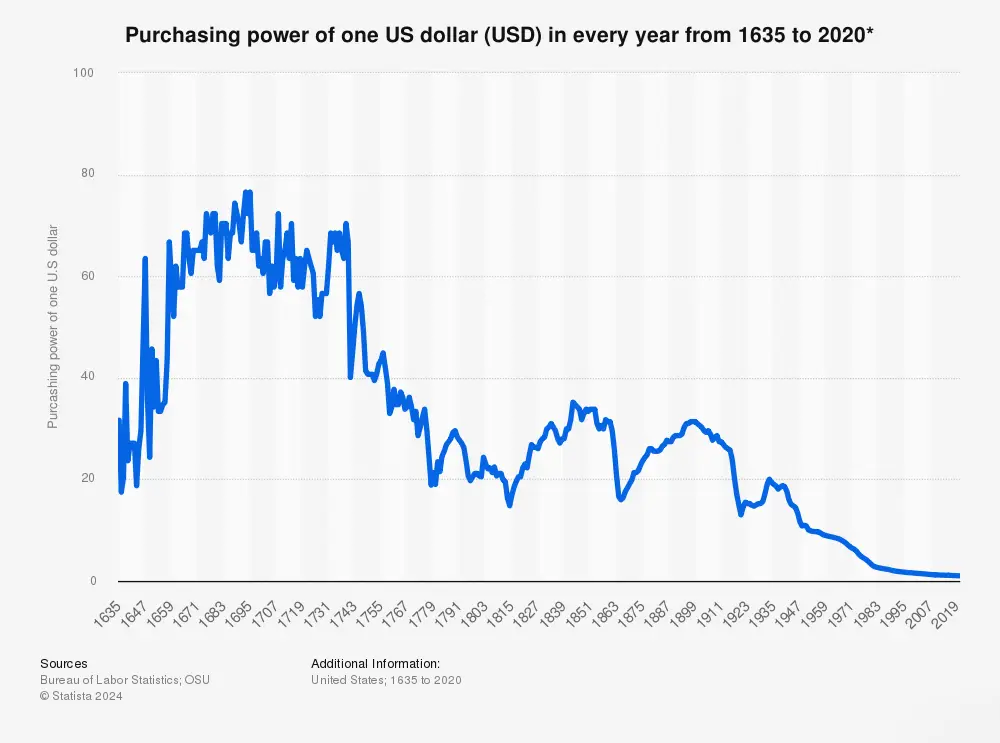

When converted to the value of one US dollar in 2020, goods and services that cost $1 in 1700 would cost just over $63 in 2020, this means that one dollar in 1700 was worth approximately 63 times more than it is today.

To illustrate the devaluation of the dollar, an item that cost $50 dollars in 1970 would theoretically cost $335.50 US dollars in 2020 (50 x 6.71 = 335.5), although it is important to remember that the prices of individual goods and services inflate at different rates than currency, so this graph must only be used as a guide.

$1 in 1900 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $37.54 today, an increase of $36.54 over 124 years. The dollar had an average inflation rate of 2.97% per year between 1900 and today, producing a cumulative price increase of 3,653.58%.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics consumer price index (which we will discuss later), today’s prices are 37.54 times as high as average since 1900.

The inflation rate in 1900 was 1.20%.

The current inflation rate compared to the end of last year is now 2.44%.

If this number holds, $1 today will be equivalent in buying power to $1.02 next year as the dollar continues to lose value over time.

This chart shows the buying power equivalence for $1 in 1900 (price index tracking began in 1635). For example, if you started with $1, you would need to end with $37.54 in order to adjust for inflation (sometimes referred to as “beating inflation”).

Alas, whenever a country goes off the gold standard to a pure fiat system it becomes irresistible to just keep the printers pumping out more and more money.

Sure, it creates flexibility in monetary policy but it almost always leads to gross misuse.

In modern times, money is always issued along with debt in the same amounts.

The results are often disastrous, with Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Germany in the 1920’s serving as prime examples.

The currency eventually becomes worthless.

But the Ponzi scheme can go on for a long time before that happens.

The US dollar has already lost 97% of its value over 50 years, and the devaluation continues to accelerate day after day, year after year.

How long can a fiat currency last without collapsing into hyperinflation?

The answer depends heavily on how much fiscal discipline the country has, how strong its economic policies are, and how much confidence the public has in the currency.

Fiat Foods

Money is an integral component of every economic transaction, and as a function, exerts massive influence on nearly every dimension of human existence.

People are free to choose anything as a money, but over time, some things will function better.

Cattle were a good choice at some point. Buckskins (aka bucks), seashells, glass beads, lime stones, too.

The things that tend to function better have better marketability, and they reward their users by serving the function of money better.

Metals were a good choice when they were more difficult to make.

But as they become more difficult to make, precious metals (gold, silver, etc.) became money.

Later, only the most precious of metals were able to survive the test of time, and gold emerged as the winner.

Now, in modern times, we use imaginary money.

And the mechanisms of this fiat currency, outlined in the previous section of this paper, create several notable distortions within the structure and dynamics of food markets.

Bear with me here because it will take some time to connect all of the dots to human health, but I promise they will.

In the next section, I will provide a focused analysis of two principal distortions: first, how fiat-induced incentives that elevate time preference influence farmland production output and consumer diet decisions; and second, how fiat-driven government financing enables an interventionist role in the food market and how this governmental overreach/expansion shapes agricultural policy, national dietary guidelines, and food subsidies.

Let’s pivot back to our old friend, President Nixon.

When President Nixon closed the gold in 1971 (as discussed above), thereby taking us off the gold standard, he relieved the U.S. government from the constraint of having to redeem its fiat in physical gold, thereby granting the government a wider scope for inflationary expansion.

Of course, this expansion in the money supply inevitably drove up the prices of goods and services, making inflation a defining characteristic of the global economy throughout the 1970s.

As runaway inflation inevitably accelerated, the U.S. government (like every inflationist regime in history), blamed the rising costs on a variety of political factors—such as the Arab oil embargo, bad actors in international markets, and scarcity in natural resources—deflecting attention and blame away from the true cause: the inflationary impact of its own monetary policies.

Now you may be wondering by now, “Jamin, it seems that inflation is a very bad thing for everyone involved, why don’t governments ever learn their lesson and stop introducing inflationary policies?”

That’s a great question, I’m glad you asked that question.

Well, the answer, like most answers in the world of economic tradeoffs, is: it’s not that simple.

You see, each time a government expands credit and spending, it creates a new group that depends on those funds.

In turn, this group leverages its political influence to preserve and even increase the spending, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that makes it extremely difficult for any politician to roll back—even if they really want to do so.

Sure, they’ll make plenty of false promises—what do you expect? They’re politicians. But remember, we’ve been living in a fiat world since 1971, and in a fiat-based system, the path to political success lies in exploiting the money supply (i.e., printing money), not in constraining it.

So, as food prices escalated into a massive political concern back in the 1970s, any attempt to control them by attacking and attempting to reverse inflation (and inflationary policies) was largely abandoned—a choice that had originally necessitated the closure of the gold exchange window.

Instead, they chose to implement a strategy of central planning in the food market, resulting in the disastrous consequences that continue to this day.

Earl Butz: “Get Big or Get Out”

President Richard Nixon’s appointment of Earl Butz as Secretary of Agriculture in 1971 marked a major turning point in U.S. agriculture.

Butz was an agronomist with ties to major agribusiness corporations.

His policies, though transformative and controversial, emphasized large-scale, high-yield monoculture farming and laid the foundation for industrial agriculture in the United States

Butz’ tenure introduced significant changes that reshaped not only the economics of farming but also the social and environmental landscapes of American agriculture.

His primary objective (of course) was to reduce food prices, and his approach was brutally direct: he advised farmers to “get big or get out,” as low-interest rates flooded farmers with capital to intensify their productivity.

His philosophy encouraged farmers to expand their operations, adopt intensive farming practices, and focus on growing a few select cash crops like corn and soybeans, incentivizing their production.

Under Butz’s direction, the USDA promoted practices to maximize output, such as:

- Crop Specialization and Monoculture: Butz’s policies incentivized farmers to focus on high-yield crops like corn and soybeans, which could be produced at scale. This approach led to a shift away from the traditional, diversified farms, which grew multiple crops and often included livestock.

- Government Subsidies and Price Supports: Butz restructured agricultural subsidies to maximize production, encouraging overproduction and ensuring farmers financial support regardless of market demand. These subsidies stabilized revenue for large farms but intensified financial pressure on smaller farms.

- Increased Mechanization and Fertilizer Use: Butz pushed heavy mechanization and the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, boosting yields but contributing to environmental issues such as soil depletion, water pollution, and biodiversity loss.

This “get big or get out” policy was highly advantageous for large-scale producers, but it was a death blow for small farms.

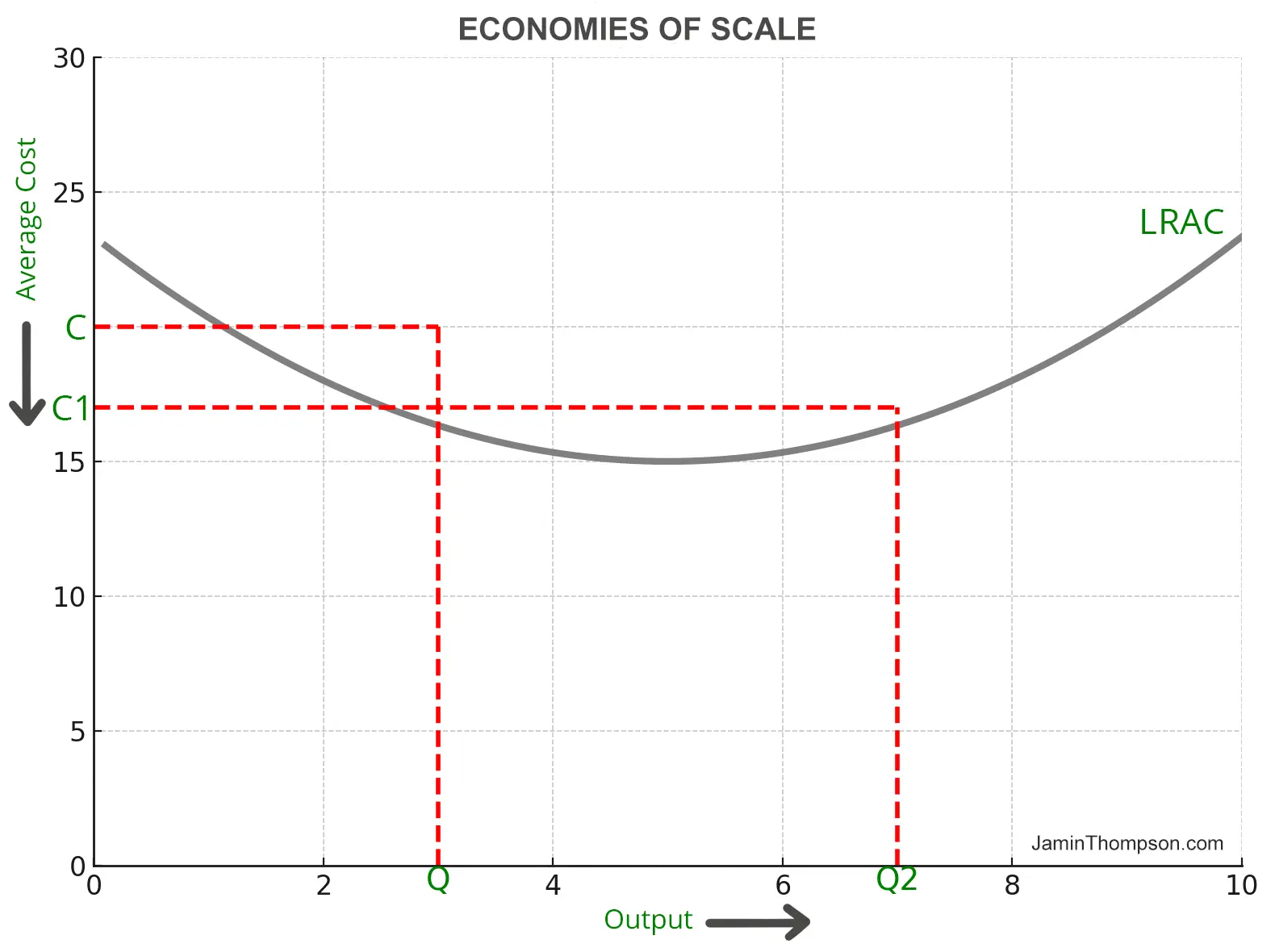

Federal subsidies and guaranteed prices drove a shift from diversified, family-owned farms to highly mechanized, single-crop operations. The approach prioritized consolidation and efficiency, benefiting large agribusinesses capable of achieving economies of scale, but it pushed smaller, diversified farms out of the market.

There were about 1.9 million farms in the United States in 2023, down from 2.2 million in 2007. While the average farm size has increased, the number of individual farms has decreased.

The policy shift marked a significant turn toward industrial-scale agriculture, emphasizing high-yield, monoculture farming to feed a growing global market.

As such, small and medium-sized farmers found it increasingly difficult to survive in an environment that rewarded scale.

Most small farmers were unable to compete or manage high debt, and were often forced out of business or absorbed by larger agribusinesses that could take advantage of economies of scale and had access to the capital needed for mechanization and high-input farming.

As a result, family farms began to decline, leading to widespread consolidation of farmland by larger corporate farming operations. Rural communities suffered as local economies contracted and traditional farming jobs disappeared.

It marked the end of small-scale agriculture and forced small farmers to sell their land to large corporations, accelerating the consolidation of industrial food production.

From 2000 onwards, the total area of land in U.S. farms has decreased annually. From 2000 to 2023, the total farmland area decreased by over 66 million acres, reaching a total of 878.6 million acres in 2023.

Not only has the land for farming been decreasing in the U.S., but so has the total number of farms. From 2000 to 2021, the number of farms in the U.S. decreased from ~2.17 million farms in 2000 to ~1.9 million in 2023.

And while the increased production did lead to lower food prices, it came at a significant cost:

- A huge decline in small-scale agriculture

- The degradation of soil quality

- The deterioration of nutritional value in American foods

This transition led to increased output but came at the cost of rural community health, soil depletion, and greater reliance on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides.

Butz’s emphasis on overproduction also had lasting consequences for the American diet and the food industry.

The massive surpluses of corn and soybeans led to the rise of low-cost, processed foods that relied heavily on these crops.

High-fructose corn syrup, corn-fed livestock, and seed oils became staples in the American food supply, contributing to the expansion of processed and fast foods and the corresponding suboptimalities in public health.

While Butz’s policies significantly boosted output, positioning the U.S. as an agricultural powerhouse and enabling large-scale food production, they also entrenched a system focused on volume over sustainability, shifting food production into a highly industrialized sector dominated by large corporations.

This shift came at a cost, with trade-offs affecting American soil health, diminishing the nutritional quality of foods, and ultimately impacting public health—consequences that would affect generations to come.

Alas, as I pointed out earlier, there is never absolute victory, there are only tradeoffs.

You see, using industrial machines on a massive scale can reduce the cost of foods, which was a key objective of Butz’s policies.

Mass production can increase the size, volume, and often the sugar content of food, but it’s a lot harder to increase the nutritional content of that food, especially as the soil gets depleted of nutrients from intensive and repetitive monocropping.

When farmers practice monocropping, the soil is depleted of nutrients over time, requiring increasing inputs of synthetic fertilizers to restore basic nutrient levels.

This creates a destructive death cycle of soil degradation and dependency on artificial inputs, which is ultimately unsustainable.

In parallel (and near perfect correlation) with the decline in the quality of foods recommended by the government, there has been a similar deterioration in the quality of foods included in the government’s inflation metric, the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—an invalid mathematical measure or statistical construct that, despite its severe flaws, is nonetheless meticulously tracked and monitored by policymakers.

For all intents and purposes (and if you are a serious economist), the CPI is a make-believe metric that pretends to measure and track over time and space the cost of an “average basket” of consumer goods purchased by the average household.

By observing and tracking price fluctuations in this basket, government statisticians believe they can accurately measure inflation levels.

The only way to agree that this is true is to have no understanding of how math works.

One must have a total fundamental disregard for the complexities of mathematical accuracy and what it means to have a “meaningful measurement”.

If you have made it this far, you are very likely a being of above average intelligence, but you don’t need to be an economics scholar to figure some of this stuff out.

A lot of basic economics often comes down to common sense.

For example, you don’t need to sit through a 90-minute macroeconomics lecture to understand that foods with high nutrition content will cost more than foods with low nutritional content.

And, as the prices of high nutrition foods increase, consumers are inevitably forced to replace them with cheaper, lower-quality alternatives.

This analysis does not require high level mathematics, it’s simply common sense.

As a common plebeian seeking to understand inflation, observing shifts in purchasing behavior—such as cheaper foods becoming a more prominent part of the ‘basket of goods’—you can see, or at least reasonably assume—depending how well you understand basic economics—that the true effect of inflation is massively understated.

For example, let’s imagine you have a daily budget of $20, and you spend the entire budget on a delicious steak that provides all the daily nutrition you need for the day. In this very simple use case, the CPI reflects a $20 consumer basket of goods.

Now, if hyperinflation causes the price of the steak to skyrocket to $100 while your daily income remains fixed at $20, what happens to the price of your basket of goods?

It cannot magically increase because you cannot afford a $100 steak with a $20 steak budget.

So, the cost of the ‘basket’ cannot increase by 5X, you just can’t afford to buy steak.

Instead, you and most others will seek cheaper, often lower-quality alternatives.

So, you make the rational decision to replace the steak with the chemically processed shitstorm that is a soy or lab meat burger for $20.

If you do this, like magic, the CPI somehow shows zero inflation.

This phenomenon highlights a fundamental and critical flaw in the CPI: since it tracks consumer spending, which is limited by price, it fails to capture the true erosion in purchasing power.

Essentially, it’s a lagging indicator which does not account for subjective value changes and the resulting substitutions in consumer behavior, causing it to understate true inflation’s impact on individual purchasing power and quality of life.

And as prices go up, consumer spending does not increase proportionately but rather shifts toward lower-quality goods.

That said, the cost of living is driven by a decline in product quality and is never fully reflected in the CPI. It cannot be reflected in the price of the average “basket of goods” because whatever you put in that basket as a consumer is determined by changes in price.

So, for the uninitiated, now you fully understand how and why prices continue to rise while the CPI remains within the politically convenient 2–3% inflation target.

As long as consumers are content to swap delicious steaks for industrial waste sludge burger substitutes, the CPI will continue to paint an artificially stable picture of inflation.

You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to “see” that by shifting toward substituting industrial waste sludge for real food has helped the U.S. government to understate and downplay the extent of the destruction in the value of the U.S. dollar in key measurements like the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

By subsidizing the production of the cheapest food options and recommending them to Americans as healthy, ideal dietary choices, the apparent scale of price increases and currency devaluation is lowered significantly.

When you look at the evolution of U.S. dietary guidelines since the 1970s, you’ll notice a distinct and continuous decline in the recommendation of meat, coupled with an increase in the recommendations of grains, legumes, and other nutritionally deficient foods that benefit from industrial economies of scale.

This trend highlights a calculated move toward inexpensive, mass-produced foods that artificially stabilize inflation metrics while cleverly hiding the true decline in food quality and customer purchasing power.

Bottom Line: the industrialization of farming has led to the rise of large conglomerates (e.g., Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland, Tyson Foods, Bunge Limited, Perdue Farms) which wield substantial political influence in the U.S., allowing them to effectively lobby for expanded subsidies, shape regulation, and influence dietary guidelines in ways that give them a competitive advantage.

Government Cheese & Diet Propaganda

Now, you may be starting to connect the dots and make the connection between monetary economics and nutrition.

As the government transitioned away from the gold standard to fiat currency, it marked a fundamental shift away from the classical liberal era and accelerated society toward a centrally planned model that favored extensive governmental control.

As such, the government now plays a massive role in food production and dietary guidelines, giving them a significant amount of control over many aspects of individual life.

This marks a fundamental shift away from trends during La Belle Époque (one of history’s most transformative periods) when governments typically refrained from intervening in food production, banning certain substances, or engaging in sustained military conflicts financed by dollar devaluation.

In stark contrast, today’s era is defined by massive government overreach, sustained warfare, and the systemic introduction of chemicals into the food supply.

Since the invention of fiat currency, governments have increasingly tried to regulate aspects of private life, with food being a prime regulatory target.

The rise of the modern nanny state, where the government cosplays as caretaker and “parent” to its citizens, providing guidance on all aspects of citizens’ lives, would not have been possible under a gold standard.

The reason for this is simple: any government attempting to make centralized decisions for individual problems would quickly do more economic harm than good and they would run out of hard money very quickly, making this type of operation unsustainable.

Fiat money, however, allows for government policy errors to accumulate over long timescales before economic reality sets in through the destruction of the currency, which typically takes much longer.

Therefore, it is no accident that the U.S. government introduced dietary guidelines shortly after the Federal Reserve began to solidify its role as America’s overbearing nanny.

The first guideline, targeting kids, first appeared in 1916, followed by a general guideline the following year—marking the beginning of federal intervention in personal dietary choices.

The weaknesses, deficiencies, and flaws inherent in centrally planned economic decision-making have been well-studied by economists from the Austrian school (e.g., Mises, Hayek, Rothbard) as they argue that: what enables economic production, and what allows for the division of labor, is the ability of individuals to make economic calculations based on their ownership of private property.

Without private property in the means of production, there is no market; without a market, there are no prices; without prices, there is no economic calculation.

When individuals can calculate the costs and benefits of different decisions (based on personal preference), they are able to choose the most productive path to achieve their unique goals.

On the flip side, when decisions for the use of economic resources are made by those who do not own them, accurate calculation of real alternatives and opportunity costs becomes impossible, especially when it concerns the preferences of those who directly use and benefit from the resources.

This disconnect highlights the inherent inefficiencies in central planning, whether in economic production, dietary choices, or broader resource allocation and public policy domains.

Before Homo sapiens developed language, however, human action had to occur via instincts, of which humans possess very few, or on physical direction and manipulation; and learning had to be done through either imitation or internal (implicit) inferences.

However, humans do possess a natural instinct for eating, as anyone observing Americans from just a few minutes old up to 100+ years of age can attest.

Humans have developed and passed down cultural practices and food traditions for thousands of years that act as de facto dietary guidelines, helping people know when and what to eat.

In such a system, individuals are free to draw on ancestral knowledge, study the work of others, and experiment on themselves to achieve specific nutritional goals.

However, in the era of fiat-powered expansive government, even the basic decision of eating is increasingly shaped by state influence.

When the state (aka the government) starts getting overly involved in setting dietary recommendations, medical guidelines, and setting food subsidies—much like the central planners the Austrian school critiqued—it is impossible for them to make these decisions based on the individualized needs of each citizen in mind (and we will discuss bio-individuality later in this text).

These agents are, fundamentally, government employees with career trajectories and personal incentives directly tied to the fiat money that pays their salaries and sustains their agencies.

As such, it is not surprising that their ostensibly scientific guidelines are heavily influenced and swayed by political and economic interests and/or pressures.

So, if you are still with me here, there are three primary forces driving government dietary guidelines:

- Governments seeking to promote cheap, industrial food substitutes as if they were real food.

- Religious movements seeking to massively reduce meat consumption.

- Special interest groups trying to increase demand for the high-margin, nutrient-deficient, industrial sludge products cleverly designed to resemble real food.

These three drivers have shaped a dietary landscape aligned more with industrial profit and ideological goals than with the health and well-being of individuals.

Let’s examine the drivers in more detail:

1) Governments seeking to promote cheap, industrial food substitutes as if they were real food.

Three well-documented cases come to mind in which the U.S. government tried to create policies that promote cheap, industrial food substitutes instead of real food:

- Margarine in place of real butter: During the 20th century, margarine—an inexpensive, industrially-produced fat—was promoted as a healthier alternative to butter. In the 1980s and 1990s, federal dietary guidelines advised Americans to reduce saturated fat intake, and recommended switching from real butter to an industrial sludge like margarine, which was made with partially hydrogenated oils. These oils contained trans-fats, which were later discovered to pose serious health risks, including a higher risk of heart disease. Margarine’s promotion reflected the prevailing views on fat and cholesterol at the time, but it inadvertently led to widespread trans-fat consumption, which is now recognized as harmful.

- High-fructose corn syrup in processed foods: High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is an industrially produced sludge derived from corn that became prevalent in the 1970s after the government implemented subsidies for corn production. The resulting low cost made HFCS an attractive sweetener for food manufacturers. HFCS began to replace real sugar (cane sugar) in various foods and beverages, including soda, snacks, and sauces. Despite limited evidence on the long-term health effects at the time, HFCS became a ubiquitous ingredient. Later research linked excessive HFCS consumption to obesity and metabolic diseases, but it continues to be a prominent ingredient in processed foods due to its cost-effectiveness and government corn subsidies.

- Fortified Refined Grains in the Dietary Guidelines: U.S. dietary guidelines have consistently pushed grain consumption propaganda, including industrial sludge grains that are heavily refined and fortified with vitamins and minerals as a primary dietary component. The focus on affordability and fortification has made refined grains (e.g., white bread, pasta, and breakfast cereals) a staple in the American diet, and consumers are often tricked into believing these artificially fortified and nutrient depleted products are actually good for them as refined grains lack fiber and other naturally occurring nutrients. This approach has supported the availability of affordable, calorie-dense foods but often at the expense of overall nutritional quality.

Another interesting case during the same time period (e.g., the period in history when America went off the gold standard) was the strange war the government declared on eggs.

Starting in the 1960s and 1970s, fiat scientists working for the government raised alarms when they suggested that high dietary cholesterol could raise blood cholesterol levels and contribute to heart disease.

Since eggs are naturally high in cholesterol, they became a focal point of attack and criticism—a conclusion that, to an analytical thinker, should immediately raise warnings in your brain of a ‘hasty generalization’ or a ‘post hoc ergo propter hoc’ causal fallacy.

Nevertheless, to the inferior mind, correlation must always equal causation, so the fiat scientists at the U.S. government recommended new dietary guidelines limiting egg consumption.

These guidelines, aimed at reducing “heart disease risk”, led consumers to avoid eggs or seek out cheap egg substitutes, often industrially processed sludge products designed to eliminate cholesterol.

This shift was compounded by agricultural subsidies favoring crops like corn and soy, which made processed foods cheaper than unsubsidized “healthy” whole foods like eggs.

For decades these guidelines were followed almost religiously as scientific law, however, as nutritional science advanced, research revealed that dietary cholesterol has little to no impact on heart disease risk.

Many such cases illustrate how government policies and guidelines have consistently aligned with large-scale farming and industrial food production, highlighting the link between economic interests and public health outcomes.

2) Religious movements seeking to massively reduce meat consumption.

Every decision the government makes is not always based on science or sound analysis, many times, they are simply influenced by powerful or persuasive special interest groups. One little-studied, and little-discussed case is the case of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, who has maintained a longstanding 150-year moral crusade against meat.

One of the church’s founders, Ellen G. White (1827-1915), was a prominent religious leader whose writings shaped the church’s doctrine, particularly on health and dietary practices. White advocated for a vegetarian diet, viewing it as morally superior and conducive to spiritual and physical health. She claimed to have “visions” of the evils of meat-eating and preached endlessly against it.

Author’s note: There are reports suggesting White was still eating meat in secret while simultaneously preaching about how evil it was, but such claims are difficult to prove.

Nevertheless, White’s advocacy for plant-based diets and her moral opposition to meat consumption became central to Adventist beliefs, leading the church to promote vegetarianism as a healthier, ethically superior lifestyle.

In a fiat currency system, such as the case today, the ability to shape political processes can translate into substantial influence over national agricultural and dietary guidelines.

As such, White’s propaganda and influence expanded beyond church walls through Adventist-established institutions like hospitals, universities, and health institutions such as the American Dietetics Association, particularly those in “Blue Zone” communities where plant-based diets are widely adopted.

Adventists have made lobbying efforts that advocate for plant-based nutrition for years.

The church’s involvement in medical and public health fields, including the Adventist Health System and Loma Linda University, has allowed it to (1) promote vegetarianism within mainstream health and wellness discussions; (2) have their research cited in prominent health journals; and (3) influence consumer attitudes and shape public perception and policy.

I have no problem (ethically, morally, personally, etc.) about anyone, religious or otherwise, following whatever diet their visions tell them to follow, but conflict and chaos always seem to arise when these folks try to impose their views on others, or worse, use them to influence broader public policy.

Author’s note: The American Dietetic Association (now the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics), an organization which to this day holds significant influence over government diet policy, and more importantly, is the body responsible for licensing practicing dietitians, was co-founded in 1917 by Lenna Cooper, who was also a member of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. During World War I, she was a protégé of Dr. John Harvey Kellogg at the Battle Creek Sanitarium, an institution with strong Adventist ties advocating for vegetarian diets and plant-based nutrition.