On this joyous spring day of the year 2025, under the silent watch of the stars and the scroll of time, I set these words to record—not merely as commentary, but as witness.

We stand poised between two epochs: with one hand grasping the crude stone of our Neanderthal past, and the other reaching toward the blinding fire of the Singularity.

And at any moment, a single act of consequence may launch us into the uncharted future—or cast us backward into the long night of civilizational forgetting.

And it is in this strange interstice that the United States now finds itself—at a narrowing crossroads, its economic dominion trembling beneath the burden of a $37 trillion debt, rising prices that corrode the soul of the common denizen, and a dollar that once reigned supreme across the earth but now quivers beneath the weight of its own contradiction.

Once the axis of global confidence, now besieged by doubt.

Once hegemon, now stumbling beneath its own design.

Once unquestioned, now laid bare to the winds of reckoning.

These crises—woven together like threads in a fraying tapestry—unfold not merely in the courts of power or among the stewards of commerce, but sweep across the polis itself, unsettling the order of common life.

Beneath the banners of empire and the illusions of prosperity, a deeper disquiet stirs.

The laborer in the fields of Ohio, the pedagogue in the plains of Texas, the elder resting in the warmth of Florida—all now contend with forces beyond their shaping.

Their coin grows weaker, their savings wither, and the fruits of honest toil grow distant, as if the promise of the Republic has been bartered away in silence.

The dream once spoken in every tongue of liberty and plenty now fades like breath upon a mirror—seen, but not held.

As the republic now drifts amid tempests of its own making, the thread of its unraveling leads not to chance, but to a hidden fissure woven into the very fabric of the world’s monetary order—a contradiction ancient in nature, known in our time as Triffin’s Dilemma.

A Republic in Chaos

The U.S. national debt, now a staggering $37 trillion, casts a long and ominous shadow over the nation’s economic stability.

This colossal figure, accumulated over decades of borrowing and sloppy fiscal policy, has reached unprecedented levels.

Annual interest payments alone have ballooned to $1.4 trillion this year, a burden that is now beginning to reshape the nation’s fiscal priorities.

Figure 1: U.S. gross federal debt (total national debt) from 1970 to 2025. The debt has soared exponentially since the end of the gold standard in 1971. In 1970, U.S. debt was only about $0.37 trillion. It doubled in the 1970s and kept climbing, reaching $5.7 trillion by 2000 and $13.6 trillion by 2010. After the 2008 financial crisis and especially after 2020’s pandemic spending, the debt accelerated sharply – rising from $26.9 trillion in 2020 to over $36 trillion in early 2025

As budget data shows, interest expense now surpasses defense spending ($850 billion) and is on track to overtake Social Security ($1.6 trillion), consuming an ever-larger—and increasingly unsustainable—share of federal resources.

The debt’s growth and trajectory reflect the long-term result of deficit spending and fiscal imbalance, where the government has consistently spent more than it collects in revenue and bridging the gap through borrowing.

For the average American, the consequences are far from abstract.

This mounting debt translates into a clear, present, and tangible danger to their financial security and quality of life, opening the door to a wide range of economic vulnerabilities.

Figure 2: U.S. debt interest surges past defense spending in 2025, nearing social security as the largest budget item. Interest on the debt is projected to surpass social security as the #1 outlay by 2027.

To address this growing fiscal disaster, policymakers are faced with two politically treacherous options: either raise taxes or cut spending on essential programs to manage its obligations.

Both options are economically painful, though the tradeoffs may differ depending on which political and/or economic theory you ascribe.

At the root of this mounting crisis is a little-known and rarely discussed structural Catch-22 embedded in the international monetary order called Triffin’s Dilemma.

Triffin’s Dilemma (also known as the Triffin Paradox) is an economic theory that highlights a fundamental conflict of interest in the global monetary system when a single country’s currency serves as the world’s primary reserve currency.

It reveals a structural flaw that has driven the U.S. to this precarious edge.

The dilemma emerges from the contradiction between two obligations.

Specifically:

- Global Liquidity Needs: To support global trade and finance, the world needs ample reserves of the dominant currency. This forces the issuing country to run persistent trade deficits, effectively exporting its currency to other nations by importing more goods and services than it exports.

- Confidence in the Currency: However, those same deficits erode trust in the currency’s long-term value. As dollar balances accumulate abroad, foreign holders begin to question its sustainability—fearing depreciation, instability, or even abandonment as the reserve standard—leading to a loss of its status as the trusted global reserve.

Author’s Note: The United States, as the issuer of the global reserve currency, is trapped in a conflict between supplying enough liquidity to keep the system running and preserving confidence in the dollar itself. It’s a conflict between global liquidity needs and currency stability. This is Triffin’s Paradox in action.

The U.S. must export and flood the world with dollars to lubricate global trade, but doing so fuels debt and weakens the dollar’s credibility over time.

This vicious cycle (or necessity) has helped inflate the $37 trillion national debt and the crushing interest burden that accompanies it.

Figure 3: U.S. federal outlays in the first 7 months of FY2024 – Net interest on the debt (red) was about $514 billion, slightly more than defense spending (≈$498 billion) and not far behind Medicare (≈$465 billion). Social Security remains higher ($837 billion over the same period), but the rapid rise in interest costs is notable. In FY2023, net interest outlays ($659 billion) nearly doubled from 2020’s level (~$345 billion). This reflects higher debt and rising rates – interest is now the second-largest line item after Social Security, exceeding defense

This pattern of deficit-financed liquidity export and monetary expansion has chipped away at the dollar’s strength and stoked inflation, threatening the very trust that underpins its reserve status.

In short, Triffin’s Dilemma reveals the structural contradiction that underlies the U.S. monetary regime: to supply the world with dollars (and facilitate global trade) the U.S. must borrow and print—but that very act undermines the system’s foundation.

And now, the consequences are starting to catch up.

This is not just an academic paradox; it’s the structural time-bomb under the U.S. economy. And after decades of complacency and good times, the explosion is now imminent.

Now the U.S. is trapped: the conflict and inherent contradiction between providing global liquidity and maintaining domestic economic health has set the stage for economic disaster.

And that impending disaster is now threatening the livelihood and longevity of not only the common man, but also the United States’ economic hegemony.

That said, some more Keynesian leaning economists have long treated Triffin’s Dilemma as a manageable problem–something to be finessed with policy tweaks, deficit spending, and multilateral coordination.

But in my view, it is fundamentally impossible to have a “sound” national economy when the currency is endlessly printed to meet global demand.

To me, the dilemma reflects an unsustainable framework—one where domestic priorities are perpetually sacrificed to support global liquidity.

I support a more cautionary view: fiat money systems cannot maintain long-term credibility if they’re built on endless credit expansion.

As such, Triffin’s Dilemma isn’t a temporary challenge—it’s the structural consequence of issuing a reserve currency without any tether to tangible value.

So, there is a clash in philosophy between mainstream economists and the economists who still follow the old ways.

And so, what we are witnessing today is not an economic puzzle in need of smarter management or more centralized controls—it is the unraveling of a monetary system whose contradictions were baked in from the beginning.

How Did We Get Here?

To understand today’s crisis, we must start at Bretton Woods in 1944.

In the post-WWII Bretton Woods system, the U.S. dollar was installed as the world’s reserve currency–pegged to gold at $35/oz, while other nations pegged their currencies to the dollar.

The U.S. was required to maintain this peg by ensuring convertibility between dollars and gold, effectively giving the dollar a gold backing and making it the linchpin of global trade.

However:

To provide global liquidity, the U.S. had to run deficits. As dollars accumulated overseas, foreign nations began to question whether the U.S. had enough gold to back them, triggering a crisis of confidence.

Triffin pointed out this fatal flaw in the late 1950s: if the world was to grow and trade, it needed more dollars in circulation.

But issuing more dollars meant running balance-of-payments deficits (i.e. ship dollars abroad), which would eventually undermine trust in the dollar’s convertibility to gold.

Yet accumulating these deficits would eventually make other countries lose faith that the dollar was as good as gold.

Triffin predicted the system would break—and he was right.

By the late 1960s, U.S. gold reserves were dwindling as trade partners—most notably France under de Gaulle—demanded gold in exchange for their growing dollar holdings.

The U.S. had been issuing more dollars than it could redeem at the promised gold rate.

And this tension culminated in the collapse of Bretton Woods. In 1971, facing a run on Fort Knox, President Nixon suspended the dollar convertibility to gold.

This “Nixon Shock” marked the first grand manifestation of Triffin’s Dilemma: the U.S. defaulted on its external gold commitment to preserve domestic liquidity.

To put this plainly, America chose to debase the dollar rather than restore sound money.

The result was a pure fiat currency—unconstrained by gold, yet still the world’s primary reserve asset.

This set the stage for decades of trade deficits, money printing, and monetary distortion that all led to our current predicament.

50 Years of Deficits and Debasement

Once the dollar was freed from gold, its role as the global reserve currency became both a blessing and a curse, a double-edged sword.

On one hand, it conferred an “exorbitant privilege” on the United States, enabling Americans to consume beyond their means by issuing dollars and running persistent trade deficits without impunity.

And on the other hand, that privilege demanded a price: permanent imbalances and creeping fragility.

Since 1975, the U.S. has run a trade deficit every single year—2025 marks the 50th consecutive year.

Triffin’s Dilemma demanded this arrangement: the world needed dollars to facilitate trade, and America obliged by buying more from abroad than it sold, year after year.

Trillions of U.S. dollars piled up overseas, especially in foreign central banks and sovereign wealth funds.

Meanwhile, domestic industries hollowed out, factories shut down, and the external debt ballooned.

Mainstream economists (mostly Keynesians) often downplayed these deficits, arguing that they were benign, attributing them to capital inflows, investment demand, and the attractiveness of U.S. financial markets.

But economists who still followed the old ways saw a different story: chronic deficits were seen as glaring red flags, symptoms of an unsound and unsustainable monetary regime reliant on financial engineering, fake money, and overconsumption.

Internally, the government embraced the same bad habit—spending far beyond its means, confident that the dollar’s global reserve status would spare it from the typical consequences of overspending.

Washington racked up a colossal national debt (around $37 trillion at the time of this writing) and paid for endless military engagements with borrowed money.

The money supply (M2) exploded by roughly 40% between 2020–2022 alone—a stunning acceleration justified under the guise of pandemic relief but emblematic of the deeper addiction to fiat liquidity—and enabled by the Federal Reserve’s willingness to “support the economy” at all costs.

And sure enough, the bill came due.

Inflation surged to 40-year highs in 2022–2023, hitting 9%, and ravaged American consumers’ purchasing power.

The very people the fiat system was supposedly designed to protect were now paying the price.

As their real incomes shrank, so did confidence in the dollar.

A classic display of monetary debasement in real time.

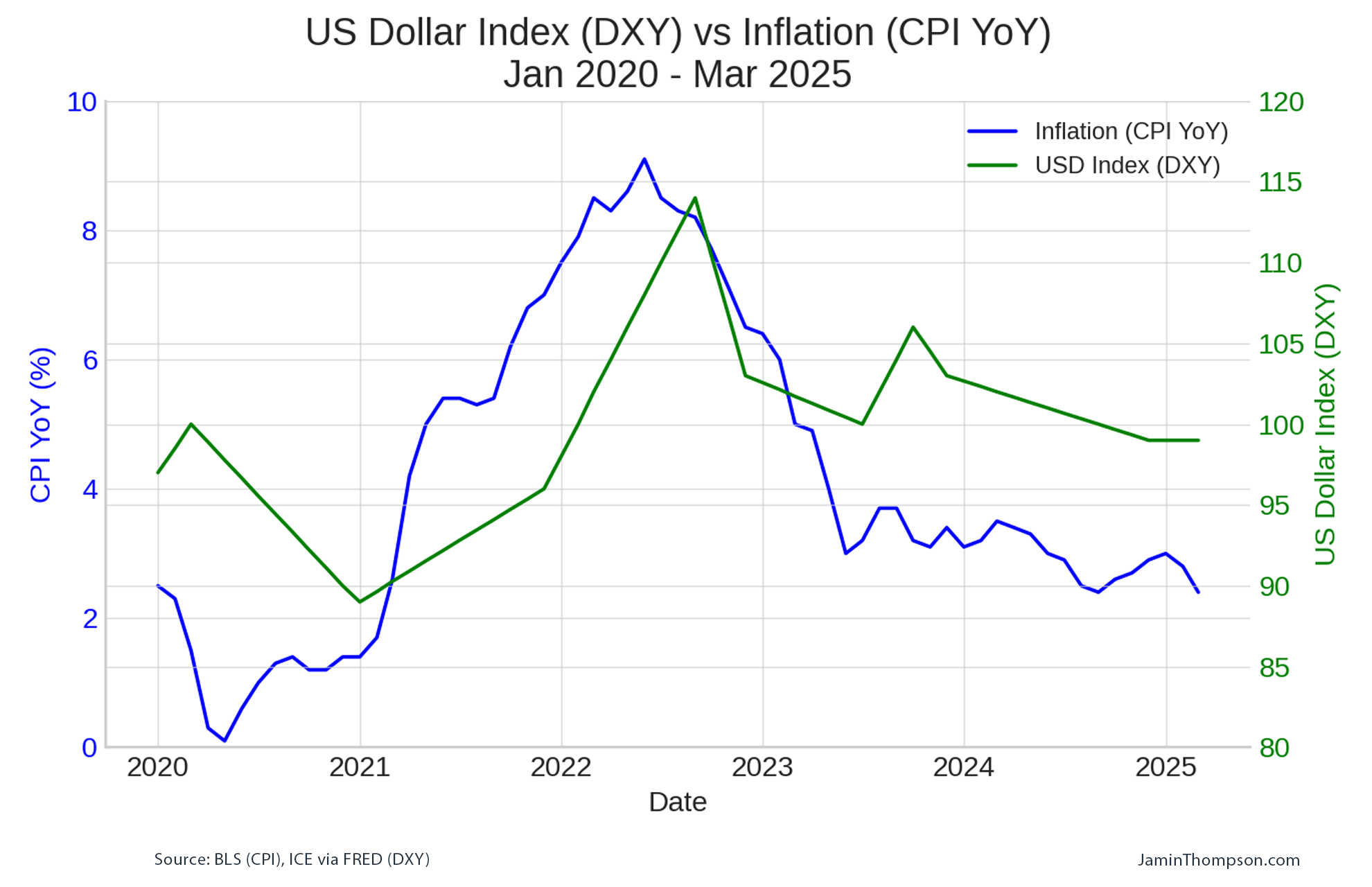

Figure 4: The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) (green line, right axis) vs. annual CPI inflation (blue line, left axis) from Jan 2020 to Mar 2025. After the pandemic hit in 2020, the Federal Reserve’s easy money helped push inflation from ~0% to 9% by mid-2022–the highest in 40+ years. In response, aggressive Fed rate hikes drove the dollar’s value up sharply: the DXY surged to a 20-year high around 114 in Sept 2022 (even as U.S. inflation was peaking). Subsequently, as U.S. inflation has come down (to ~3-4% in 2023) and the Fed slowed hikes, the dollar index eased back toward 100 in 2023–2024. By early 2025, DXY ~99 and inflation ~2.4%

The very middle-class Americans the fiat-dollar system was ostensibly meant to help were instead seeing their savings eroded and cost of living skyrocket.

In the eyes of many traditional (old school) economists, this was no coincidence but cause and effect: decades of easy money and deficits (to uphold the reserve currency illusion) were finally resulting in the devaluation of the dollar and the pain that always inflicts on ordinary people.

Author’s Note: Today, the U.S. dollar remains the dominant global reserve currency, and Triffin’s Dilemma still applies: The U.S. runs persistent trade deficits, supplying dollars to the world. This has led to debates about the sustainability of the dollar’s dominance, with some pointing to rising U.S. debt and geopolitical shifts as potential threats. Alternatives like the euro, Chinese yuan, or even cryptocurrencies have been proposed, but none have displaced the dollar so far.

Simplified Example: Imagine a small town where one shop’s IOUs are used as money by everyone. The shop must keep issuing more IOUs to keep the town’s economy growing, but if it issues too many, people might doubt the shop’s ability to honor them, causing the system to collapse. In essence, Triffin’s Dilemma reveals an inherent instability in any system where one nation’s currency underpins global finance—it’s a balancing act that’s tough to sustain indefinitely.

2025: The Year of Reckoning

As we enter 2025, the consequences of these long-running imbalances are coming due with a vengeance.

The U.S. federal debt has swollen to levels once unimaginable–and crucially, servicing that debt is becoming impossible to ignore.

Figure 5: Net interest on the federal debt (which is less than the actual total interest on the debt) was the second highest outlay in March, more than all health spending combined, or more than national defense – only Social Security was more, but the gap is closing fast.

Annual interest payments on the debt are projected around $1.4 trillion, a burden rivaling even the Pentagon’s budget.

In fact, by 2024 interest costs (nearly $870 billion) had already eclipsed what America spends on national defense–a stunning milestone that lays bare the government’s priorities: past borrowing now costs more than current military security.

Rising interest rates (the Federal Reserve’s belated response to inflation) have turned the debt pile into a ticking time-bomb.

Each uptick in rates feeds directly into higher interest expense on new and rolling debt.

The Treasury is essentially paying compound interest on decades of Keynesian “borrow and spend” policies.

The Keynesians once promised that deficits wouldn’t matter so long as interest rates stayed low–but those low-rate days are gone.

Now the bill is coming due, and it’s eating the federal budget alive.

Figure 6: U.S. interest on national debt vs. defense spending (2000–2025) – Interest payments on the national debt (orange) are projected to reach $1.4 trillion in 2025, surpassing defense spending (blue) at $860 billion. This marks a critical fiscal inflection point: interest has overtaken defense as a budget priority. From 2000 to 2020, both lines rose gradually, but interest spending entered a hyper-acceleration phase post-2021—fueled by record debt and rising rates. The widening gap illustrates the growing burden of servicing debt in a high-rate, high-deficit environment, with implications for future federal priorities.

Author’s Note: To maintain global dollar supremacy and sustain demand for USD, we had to export inflation and import rot and decay. That was the Triffin tradeoff—but the cost of that privilege is compounding. And now we’re in a deep debt death spiral—borrowing to pay interest on the borrowing, feeding a system that can only survive by eating itself. The fiat endgame is always the same: interest swallows the empire.

Of course, the black belts have been sounding the alarm for quite some time: when a nation’s interest payments exceed even its ability to defend itself, you know a debt crisis is at hand.

Unlike Keynesian yellow belts, who often suggest the U.S. can grow its way out of debt or inflate it away gently, the old-school grandmasters see the interest spiral as proof that the fiat Ponzi scheme is reaching its mathematical limits.

So now Washington faces an ugly choice: radically slash spending (an unlikely political outcome) or monetize even more debt (i.e. print more money to pay interest) which fuels a vicious cycle of further inflation and currency debasement.

In other words, Triffin’s Dilemma has matured into a no-win situation.

The U.S. must keep issuing more dollars to service past obligations and to maintain global dollar liquidity—but doing so only hastens the loss of trust in the currency.

It’s a feedback loop toward collapse.

In 2025, this tension is palpable. The U.S. trade deficit stands at $1.2 trillion annually, a legacy of decades of dollar exportation.

The dollar remains the linchpin of global finance—60% of international trade and 88% of forex transactions—but cracks are showing.

China and Russia, holding 4,000 and 2,300 tons of gold respectively, are diversifying away from dollar reserves, settling oil trades in yuan or rubles.

The euro and even cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin (now at $80,000) are gaining traction as alternatives.

Triffin’s prophecy looms: the dollar’s over-issuance may be its undoing.

The De-Dollarization Phase

The United States has long outsourced the consequences of its monetary excesses to the rest of the world—printing dollars without impunity while forcing other nations to absorb the inflationary blowback.

It’s an imperial arrangement masquerading as economics.

The U.S. consumes, the world produces.

We export IOUs, they ship back real goods.

Many of these nations, effectively vassal states in a dollar-feudal system, are beginning to realize that “the system” is rigged against them—that their productivity props up our deficits, and their savings finance our decadence.

And now, they’re starting to revolt against their masters.

Triffin’s Dilemma doesn’t just affect the United States domestically; it has global repercussions, and now the rest of the world is responding.

After decades of dollar dominance, many other nations are increasingly wary of the arrangement whereby the U.S. can print value at will while they must earn it.

So, in recent years, de-dollarization has accelerated–led most notably by the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) and their partners.

These countries have openly declared their desire to reduce reliance on the dollar for trade and reserves.

The motivations are both practical and geopolitical: U.S. deficits and money-printing export inflation to the world, and Washington’s habit of “weaponizing” the dollar (through sanctions or trade tariffs) has spooked many nations into seeking alternatives.

Within BRICS, trade deals are increasingly being settled in local currencies or bilateral swap arrangements that bypass the dollar.

A system dubbed “BRICS Pay” is under development to facilitate cross-border payments without using SWIFT or the U.S. banking system.

Central banks globally are stockpiling gold at a historic pace—1,045 metric tons added to gold reserves in 2024 alone, the third consecutive year above 1,000 tons.

To put that in perspective, 1,000+ tons is about 25% of annual global mine production—an enormous shift of reserves into physical metal.

This gold rush is a hedge against dollar depreciation and a potential foundation for alternative currency arrangements.

Some have floated the idea of a future BRICS reserve currency backed by a basket of commodities or gold, to further dethrone the dollar.

Whether or not a new currency materializes soon, the writing is on the wall: the dollar-centric system is fraying.

Even longtime U.S. allies have begun engaging in yuan-based energy trades or euro-based commerce to sidestep the dollar where convenient.

But the Keynesian establishment tends to dismiss de-dollarization as a minor threat—they point out (correctly) that the dollar still comprises the majority of global reserves and trade.

But you don’t need fancy charts and advanced quant to tell you these developments are harbingers of an inevitable shift.

Once confidence in the dollar wanes, a self-reinforcing exodus can occur: fewer global holders of dollars means less appetite for U.S. debt, which means the Fed must print more to finance deficits, which then further weakens the dollar’s value, driving even more countries to diversify away.

It’s a feedback loop that can rapidly accelerate—especially if a major shock (like a U.S. solvency scare or geopolitical conflict) erodes trust in U.S. financial leadership.

Notably, even the petrodollar arrangement (oil priced in dollars) is facing challenges, with key oil exporters like Saudi Arabia open to non-dollar sales under certain conditions.

In sum, the external support that has long propped up the dollar is slowly being pulled back.

Triffin’s Dilemma is reaching its breaking point internationally: the world will not indefinitely accept depreciating dollars in exchange for real goods.

And when the world diversifies en masse, the U.S. will face the stark reality that it can no longer export its inflation so freely.

Tariffs and Trade Wars

Depending on your political leanings, tariffs might evoke strong feelings one way or another.

I’ll write a more detailed post on tariffs soon, but will touch on them briefly since they contextually tie into the story.

Here, we’ll explore them through an economic lens:

1. evaluate the potential positives (growing revenue, incentivizing domestic production, securing critical industries); and

2. examine the potential suboptimalities (inflation, stagflation, inefficiency).

The goal is to remain impartial, curious, and open to possibilities.

First, let’s start with the basics.

Tariffs are taxes that:

1. Raise revenue for the country imposing them by taxing both sides—foreign exporters eat part of the cost, but domestic consumers feel it too. Who pays more depends on pricing power and demand elasticity. It’s one of the few taxes that politicians like because it’s politically useful and economically quiet.

2. Insulate/protect domestic industries and help them buy time by blocking out cheaper, foreign competition. But protection cuts both ways: it makes the companies less efficient unless you simultaneously juice demand with fiscal/monetary stimulus to keep things humming.

3. Are necessary in times of conflict or high probability of war. When major powers are on a collision course, the calculus changes. You don’t want to be reliant on rivals for semiconductors, fertilizer, or fighter jet parts. Domestic production capabilities must be assured, and tariffs help you rebuild that strategic autonomy.

4. Reduce external dependencies by shrinking current account and capital account imbalances. In simple terms: you rely less on foreign goods and foreign financing—something that becomes mission-critical when the world shifts from globalization to fragmentation, or when great geopolitical power conflict turns hot.

5. Distort comparative advantage, reduce global efficiency, and lead to less optimal production.

6. Create stagflation for the world as a whole, and, on net, they slow growth and raise prices. The exporting country sees deflationary pressure. The importing country—usually the one imposing the tariff—gets inflation. Lose-lose in aggregate.

Those are the first order consequences.

The second order consequences are all about the reaction:

a) how does the other country respond/retaliate?

b) do they move their currency?

c) does their central bank respond with looser or tighter money?

d) does their central government go into stimulus mode or pull back?

And that’s where things get nonlinear.

Author’s Note: Tariffs may appear straightforward—a tax on imported goods to raise revenue or protect domestic industries—but their effects are inherently nonlinear. Meaning, the consequences don’t scale proportionally with the policy itself. A modest tariff can set off a chain of reactions: currency adjustments, supply chain shifts, retaliation from trading partners, capital flight, or shifts in monetary policy. These ripple effects interact with complex systems—markets, institutions, expectations—and often produce outcomes far beyond what the initial policy intended. What starts as a price adjustment at the border can evolve into a full-blown systemic disruption.

At this current moment in spacetime, President Trump has ramped up his tariff plan and protectionist measures, aiming to bolster American industry and address trade imbalances.

He has threatened +100% tariffs on nations exploring alternative reserve currencies, warned BRICS countries against challenging the dollar, and put massive pressure on trade agreements like the USMCA by targeting North American partners over issues like migration.

These bold moves resonate with populist sentiments, but how might they align with—or diverge from—economic fundamentals?

Let’s dive into some potential strategic upsides.

By targeting specific imports, the government could generate funds while sidestepping the disincentives to work or investment that income taxes might create.

In today’s context of high debt and inflation, tariffs could serve as an alternative revenue source without fueling direct inflation via money printing.

Less government spending might be ideal, but if cuts aren’t feasible, tariffs could be the politically palatable middle path.

By raising the cost of imported goods, there is a chance tariffs might nudge consumers and businesses toward domestic alternatives, particularly in key industries.

By raising the cost of imported goods, tariffs might also shift consumer and business behavior toward domestic alternatives—especially in critical sectors like semiconductors and rare earth minerals.

Of course, I’d argue that this sort of strategy distorts market efficiency, as I tend to favor comparative advantage over protectionism.

But let us consider a twist to the plot: what if the goal here isn’t pure efficiency but strategic resilience?

The U.S. risks major vulnerabilities if supply chains collapse in a conflict, and tariffs can act as catalysts for domestic rebuilding.

Furthermore, tariffs could be a proactive move to secure supply chains and shore up critical industries against global uncertainties—such as the steadily rising risk of World War 3.

Rare earth minerals and semiconductor chips—vital for technology and defense—are heavily imported, often from geopolitical rivals (notably China).

Tariffs on these could incentivize U.S. firms to build domestic capacity, reducing reliance on foreign supply chains.

The danger here would be a future conflict where access to these resources is cut off; so a tariff-driven domestic base might prove invaluable.

Of course, I’d argue that markets naturally adjust to risks, but businesses often prioritize short-term profits over long-term security.

So, incentives need to be aligned.

That said, tariffs on foreign rare earths or chips could encourage investment in American mining and manufacturing, ensuring self-sufficiency if supply chains collapse.

And while this approach does sacrifice some peacetime efficiency, the trade-off may be justified for national security—one of the rare cases where even a strict free-market purist might concede a limited role for the state.

It’s an uncomfortable but rational concession, even for someone who typically sees the state as a net destroyer of value.

I digress.

Tariffs also serve as diplomatic tools and can give you leverage in trade negotiations.

Trump may use them to pressure other countries into opening their markets, improving intellectual property protections, or negotiating fairer trade terms.

If successful, temporary distortions could lead to freer trade down the road.

They could also be used to neutralize foreign subsidies and dumping practices, which distort global markets in favor of state-backed industries.

Despite these potential gains, tariffs come with clear costs.

They raise prices for American businesses and consumers, especially since over half of imports are intermediate goods.

Higher input costs reduce profit margins or increase consumer prices.

The 2018-2019 tariff skirmishes demonstrated this effect, and 2025’s new wave could amplify it.

Retaliation is also a risk.

Trade wars shrink global markets and slow growth.

The trade deficit—often a tariff target—is rooted in monetary and fiscal causes (like dollar overvaluation and overspending), not trade mechanics.

Tariffs won’t resolve these root problems.

They may only mask the issues.

At the end of the day, nobody can read Trump’s mind, but it looks relatively clear that these tariffs are more than just basic populist flexing.

We can reasonably assume the goal(s) are to:

- grow revenue without domestic tax hikes

- bolster strategic industries

- prepare for geopolitical shocks, and

- reshape trade dynamics

Of course, these interventions clash with free-market ideals, yet the potential upsides invite curiosity.

Do the benefits of resilience or leverage outweigh the costs of distortion?

It goes without saying: the U.S. government needs to figure out some short-term fixes to stop the bleeding—but in terms of the raw economics, there is a high likelihood tariffs could backfire.

These moves, while playing to populist sentiment, are viewed by many economists as counterproductive and inflationary.

Why inflationary?

Because it’s “easy money” policy dressed up in disguise—instead of printing money, tariffs attempt to paper over structural issues by forcefully shifting the terms of trade.

Of course, the Keynesians usually defend some tariffs as bargaining chips or necessary to protect jobs (they will never admit this while Trump is president, but these are their core fundamentals) but old-school economists still see this as treating symptoms while worsening the underlying illness.

The trade deficit is not going to disappear because of tariffs; it exists because of monetary and fiscal factors (chiefly, the overvalued dollar and American overspending).

So, until those root causes are addressed (i.e. until the U.S. stops flooding the world with dollars), tariffs are just distortions that ultimately make consumers poorer.

And now, a deeper irony emerges: a government that inflated the currency for years is now imposing tariffs that hurt consumers yet again.

Both of these problems stem from the same fallacy—the belief that government manipulation can produce prosperity, whether through printing money or by micromanaging trade.

But neither of these things address the fundamental need for a real economic restructuring toward the things that matter: savings, production, and balanced budgets.

So, until the U.S. addresses its spending addiction and currency overissuance, tariffs are just another band-aid on a broken system.

That said, I do give Trump credit, he has pretty good instincts.

He mixes populist appeal with hard-money rhetoric—he’s floated ideas like a gold standard and auditing Fort Knox.

He knows he can’t go full Austrian in a Keynesian framework, but his maneuvers suggest he knows he’s playing a complex game.

None of it, however, solves Triffin’s Dilemma.

Foreign retaliation to de-dollarization penalties could accelerate the rise of alternative trading blocs and undermine dollar hegemony even faster.

So, while tariffs might offer short-term tactical utility, they also carry strategic risk.

In the long run, they may make inflation worse and global trust weaker.

Sure, they may temporarily stop the bleeding and shift some supply chains, but none of it will mean much if this administration still decides to run large deficits and conjure growth through protectionism.

Author’s Note: If foreign nations are hit with U.S. tariffs as punishment for de-dollarizing, it may incentivize them further to create alternative trading blocs and currency arrangements that exclude the dollar. So, a trade war could just be a short-sighted or short-term “fix” that could accelerate the end of dollar hegemony while making domestic inflation worse—truly a lose-lose, as most well-trained economists would predict.

At the end of the day, tariffs probably won’t fix deep structural economic problems, but in narrowly defined scenarios—like national security or global instability—they might offer strategic utility and pragmatic gains.

The real test lies in whether nations can weigh ideology against necessity without losing the plot and triggering more instability.

Fort Knox and the Gold Question

Nothing illustrates the depth of the current monetary crisis quite like the renewed focus on gold.

For decades, gold has been dismissed by mainstream economists as a “barbarous relic,” irrelevant to modern finance.

Yet here we are in 2025, and gold is back in the conversation at the highest levels.

President Trump (hardly a paragon of monetary orthodoxy) and his sidekick Elon have called for a full audit of U.S. gold reserves in Fort Knox.

With massive skepticism growing about the stability of the U.S. dollar, it’s no surprise—but for those familiar with the teachings of the old masters (Menger, Mises, Hayek, Rothbard, Böhm-Bawerk, etc.), a return to sound money is more principle than provocation.

Calls for an audit come not from conspiracy but from a desire to restore confidence in a fiat regime increasingly viewed as unstable.

But for the uninitiated, if you’re wondering “why audit Fort Knox now?”, the answer is simple: because an increasing number of Americans (and foreign creditors) quietly suspect that the emperor has no clothes.

And that U.S. government’s claims of total gold holdings (8,133 tons officially) and roughly 4,580 tons, worth $486 billion at $3,300/oz in Fort Knox, might not tell the whole story.

After all, the last comprehensive audit of Fort Knox was in 1953, right after Eisenhower took office.

Since then, there have been only occasional peeks—a 1974 Congressional visit, a 2017 photo-op with Treasury Secretary Mnuchin—but no thorough accounting.

The government tells us that there’s gold inside, however, doubts linger: how much of this gold is physically present? And perhaps more importantly, how much is economically unencumbered?

Naturally, this opacity has fueled conspiracy theories—claims that the gold has been secretly sold, leased out, or replaced with fakes.

But even if these remain unproven, their very proliferation signals a deeper issue: a crisis of confidence.

In a sound money system, no one would care this much about what’s inside Fort Knox.

But in a system built on illusion, perception, and trust, the symbolism of Fort Knox becomes paramount.

And in today’s climate of fake money, printing, and inflation, trust is evaporating, and people are grasping for any tangible assurance of value.

Gold has always served as a restraint on the state’s impulse to inflate.

The Bretton Woods era (flawed as it was) at least imposed a degree of discipline—until it snapped in 1971.

Once that link was severed, debt and money printing surged, just as the old masters predicted.

Now, even U.S. officials are implicitly admitting the old masters were right: by contemplating a gold audit (and even floating ideas of revaluing gold on the government’s balance sheet).

And should the gold be found intact, it could, in theory, be re-pegged—perhaps at $10,000/oz—bolstering confidence in the dollar.

Conversely, an empty or encumbered vault would trigger a massive confidence shock, crashing the dollar and validating years of warnings from the ancient teachings.

Either way, the very fact we’re talking about Fort Knox’s contents in 2025 shows how bad the situation has become.

Symbolically, America lost a huge portion of its gold to Triffin’s Dilemma once already—between 1945 and 1971, U.S. gold reserves fell from ~20,000 tons to about 8,000 tons as dollars were redeemed for gold by skeptical foreigners.

That was the original “gold drain” that prompted Nixon’s action.

Today’s gold drain is more psychological than physical—trust is what’s being extracted. Meanwhile, bullion flows steadily eastward as countries like China, Russia, Turkey, and Poland quietly build their stockpiles.

The U.S. hasn’t lost its official gold yet, but it may be losing something even more important—the credibility that those bars in Fort Knox once provided.

As one mining industry report noted, there is a perception that Fort Knox houses one of the largest gold reserves in the world; if an audit revealed less gold reserves than claimed, it would “send shockwaves through global markets” and likely tank the dollar in a massive selloff.

In short, the dollar might not be backed by gold anymore, but the perception that the U.S. has massive gold reserves still underpins a degree of confidence.

If we lose that, the whole fiat facade crumbles.

And an empty vault would shatter confidence in the U.S.’s fiscal stewardship, accelerating Triffin’s predicted crisis of faith in the dollar.

Even if the gold physically remains, a more insidious threat looms: encumbrance.

If it has been leased, rehypothecated, or pledged multiple times as collateral, its usability is compromised.

Encumbered gold might sit in the vault—but it is, in economic terms, already spoken for.

From a sound money perspective, this distinction matters.

Possession does not equal control.

Confidence in the U.S. reserve system rests on the assumption that gold reserves are available—not just physically present, but legally and economically free of claims.

As gold prices surge—hitting $3,357/oz in April 2025—the market is clearly signaling a loss of confidence in fiat.

If Fort Knox’s gold is found to be lacking in any way, either physically or via encumbrance, the consequences would be swift and severe.

The dollar may not be gold-backed, but its credibility is still partially tethered to the perception that gold reserves support it.

Undermine that perception, and the entire fiat facade could begin to unravel.

If There Is No Gold in Fort Knox, How Will This Affect the Dollar and U.S. Dominance Over the World?

In April 2025, gold prices soared to an all-time high of $3,357.57 per ounce—reflecting not just inflation fears or a flight to safety in times of uncertainty, but an accelerating loss of confidence in fiat currencies.

And while the dollar technically no longer needs to be backed by gold to function, its association with gold remains a powerful psychological anchor.

Figure 7: Real price of gold (1960–2025) in constant 2010 USD. After the U.S. ended Bretton Woods in 1971, gold’s price was freed from its $35/oz peg. The 1970s saw gold surge – amid inflation and oil shocks, gold spiked to record highs around 1979–1980. Following a pullback in the 1980s–90s, gold rose again in the 2000s (dot-com bust, 9/11, and 2008 crisis drove safe-haven demand). In 2020, during the COVID-19 crisis, gold jumped again, breaching nominal record highs (~$2,000/oz) as investors sought stability. By 2023–2024, gold hovered near all-time highs, reflecting currency debasement fears. In April 2025, gold reached a new all-time high of $3,357/oz, underscoring growing concerns about fiat devaluation, rising global debt burdens, and a shifting geopolitical landscape.

But the question isn’t simply whether the gold is physically present at Fort Knox.

The deeper issue is whether it’s unencumbered—freely available, not leased out, pledged as collateral, or double-counted across multiple balance sheets.

Even if the bars sit untouched in the vault, gold that’s been hypothecated is already economically claimed.

This distinction—between possession and control—is what matters most.

If markets discover that the U.S. has overstated its true gold position, the impact could be severe.

The immediate effect could be:

1. Confidence Shock: A credible revelation that U.S. gold reserves are depleted—or significantly encumbered—would be interpreted globally as a signal of fiscal mismanagement or strategic deception. The dollar’s reputation as a trustworthy reserve asset would erode, potentially triggering a cascade of foreign divestment. Conspiracy theories (e.g., the gold has been quietly liquidated or rehypothecated) could exacerbate the crisis of confidence. This wouldn’t just be about a scandal—it would be a symbolic unmasking of decades of fiscal illusion.

2. Dollar Depreciation: A collapse in confidence may prompt a global sell-off of dollar assets, placing downward pressure on the currency. The initial drop in the dollar’s value might be modest (say, 5–10%), but if paired with broader instability—like a debt crisis or geopolitical shock—it could spiral into a deeper currency event.

3. Gold Price Spike: In response to shaken trust, investors and central banks would likely flock to gold, driving prices up dramatically—possibly exceeding $10,000 per ounce. This flight to safety would further undermine the dollar’s purchasing power and amplify the shift toward hard assets.

Author’s Note: Of course, the fundamental question remains: is the gold actually there? But there’s a second, less-discussed—and arguably more systemic—risk worth considering: how much of that gold is unencumbered and/or leased out on multiple balance sheets. In other words, even if the bars are physically present, how much of it is truly available and not already pledged, leased out to bullion banks, or double-counted across balance sheets as collateral. Encumbered gold may sit in the vault, but economically it’s already claimed. From a sound money perspective, this blurs the line between possession and control—and erodes confidence in the reserve system itself. In the end, it’s not just about how many ounces there are. It’s about who actually owns them.

The U.S.’s global dominance rests on economic power, military might, and the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency (used in ~60% of global trade and ~88% of forex transactions as of recent data). No gold in Fort Knox wouldn’t directly undo this, but it could weaken key pillars such as:

1. Reserve Currency Status: The dollar’s reserve role—currently underpinning ~60% of global reserves—relies on trust. A Fort Knox scandal would provide the perfect pretext for China, Russia, or the EU to push aggressively for alternatives (yuan, euro, or a basket of currencies or cryptocurrencies). These players have already begun settling trades in non-dollar currencies, pushing harder to dethrone the dollar, and a confidence breakdown would accelerate that shift.

2. Borrowing Costs: If faith in the dollar falters, Treasuries become riskier. Yields rise. And suddenly, funding the $37 trillion national debt becomes even more difficult. As interest rates climb, more of the federal budget gets siphoned into debt service, leaving less for everything else—defense, entitlements, infrastructure.

3. Geopolitical Leverage: The dollar is arguably the most powerful weapon ever made, and its dominance gives the U.S. immense leverage on the global stage. But if countries can credibly circumvent dollar-based systems like SWIFT, Washington’s ability to enforce sanctions (i.e., against Iran or Russia) or exert pressure diminishes. A weaker dollar means a weaker empire.

4. Triffin’s Dilemma Amplifies: A Fort Knox crisis would be the ultimate stress test of Triffin’s Dilemma. The contradiction between providing global liquidity and maintaining domestic confidence would break wide open. The dollar’s over-issuance, long tolerated, would now become unsustainable.

Some realistic outcomes could be:

1. A gradual erosion of the dollar’s reserve status (say, from 60% to 40%) raising borrowing costs and reducing global influence, but not enough to trigger total collapse.

2. A multipolar currency world might emerge, where nations diversify reserves, using gold, crypto, and regional currencies, diluting U.S. dominance without replacing it.

3. A domestic fallout scenario where inflation spikes, leading to public outrage and political upheaval—especially if gold reserves were found to be overstated or encumbered.

4. A total collapse of dollar hegemony remains unlikely unless paired with broader systemic failure—the U.S. economy is too big, and no rival currency (yuan, euro) is ready to fully replace the dollar—but this cannot be ruled out entirely.

5. Finally, the most dangerous possibility: Nothing Happens. The government shrugs off the whole thing, dismisses gold as irrelevant, says “look at our GDP and military” and the markets totally buy it—sustaining the illusion, helping the dollar weather the storm. Fort Knox hasn’t had a full audit since 1953, after all, so there’s already skepticism. If the world didn’t care then, maybe it wouldn’t care now. Plus, global reliance on the dollar is sticky—there’s no quick exit.

My take: An empty or encumbered Fort Knox vault wouldn’t necessarily be the death blow to the dollar—but it would mark a profound turning point. It would shatter a key pillar of symbolic trust, accelerate de-dollarization, and reinforce the idea that America’s fiscal empire is built more on belief/illusion than on reserves. The real damage would come not from the missing gold, but from the reaction to its absence. In a fiat world running on deception and perception, confidence is everything.

Will We Ever Be Able to Solve for Triffin’s Dilemma?

The answer depends on who you ask—and which school of economics they studied under, but from my perspective, the dilemma isn’t a mysterious economic puzzle or unsolvable riddle.

It’s a predictable flaw; a built-in defect embedded in the DNA of fiat money, especially when one nation’s currency is used globally.

Triffin’s Dilemma only exists because the United States, after abandoning the Bretton Woods gold standard, began issuing a currency with no inherent constraint.

Under a real gold standard, the money supply was naturally tied to and restricted by the availability of physical gold, not government deficits or central bank printing.

But fiat money, which is the root problem, is created by government decree and backed only by trust, legal and military force, has no such limitation.

The result is a recurring conflict: the U.S., as the issuer of the world’s reserve currency, must run persistent trade deficits to supply dollars globally.

These deficits flood the world with liquidity but also erode confidence in the dollar over time.

It’s a contradiction: the more the world depends on dollars, the less stable the dollar becomes.

Fiat currency gives policymakers the illusion of control.

But this flexibility—the ability to print at will—is the very mechanism by which confidence is ultimately destroyed.

It enables overspending and chronic deficits.

It also creates moral hazard.

America consumes more than it produces, runs up debt, and creates/exports inflation to maintain its global role.

That may buy time, but it builds fragility into the system.

From a monetary integrity standpoint, reserve currencies are inherently flawed.

They grant privilege without discipline.

The United States, by issuing the reserve currency, has enjoyed what de Gaulle called an “exorbitant privilege.”

But that privilege comes at a cost: artificial demand, distorted market signals, overextension, malinvestment, systemic imbalances, unsustainable debt, and cascading cycles of boom and bust.

Triffin’s Dilemma highlights that contradiction clearly.

The Fed can either print dollars to support the global system or defend the dollar’s purchasing power—but not both.

You can have global liquidity or sound money.

Not both.

And every attempt to split the difference leads to more debt, more distortion, and ultimately, more instability.

So, can we solve it?

Yes—but not if we stay within the current fiat framework.

Solving Triffin’s Dilemma requires removing the root cause: the fiat system.

The only credible solution I see at this point is a return to sound money.

A 100% gold-backed system would eliminate the dilemma at its core.

Trade imbalances would self-correct through gold flows, not bureaucratic intervention or debt issuance.

Governments couldn’t spend beyond their means, and the money supply would be tied to real-world constraints, not central bank whim.

The dollar’s role as the global reserve currency would be over—but so would the global instability that comes from relying on an overleveraged currency.

Of course, that solution is politically unthinkable right now.

Central banks are not about to give up their power.

Governments don’t want to live within their means.

And the mainstream economic establishment—especially the Keynesians—still clings to the fantasy that fiat money can be fine-tuned indefinitely with the right models.

But their models are breaking down.

And as reality reasserts itself—through inflation, debt crises, or crises of confidence—Triffin’s Dilemma will no longer be an academic curiosity.

It will be the fault line that brings the system down.

Triffin didn’t just predict a dilemma. He exposed the contradiction that eventually forces a reckoning.

And we are nearing that reckoning now.

How I See the Dilemma Playing Out

The current fiat system is not built to last—it’s structurally unsound, and we are now entering the late stages of its lifespan.

A fiat system will always collapse under its own weight.

So, it isn’t a matter of if, it’s a matter of when.

The endgame begins with a loss of confidence—triggered either by inflation, a scandal at Fort Knox, or unsustainable debt servicing costs.

When trust fades, capital flees.

There will probably be a rush to hard assets like gold or Bitcoin.

Foreign central banks will accelerate diversification out of the dollar.

The Fed will respond with more money printing to maintain liquidity, but this only accelerates the downward spiral, risking hyperinflation.

Fiat currency systems (by design) are inherently incentivized toward debasement (classic Rothbard)—and Triffin’s Dilemma amplifies this tendency.

As global dollar demand persists, the U.S. must issue more currency, accelerating and deepening the overextension.

Eventually, markets may decide to collectively reject the dollar, initiating a sell-off effect that no amount of monetary wizardry can reverse or contain.

But a smooth transition to another reserve currency (e.g., euro or yuan) is unlikely.

More probable is an era of chaos: emergency interventions, capital controls, trade breakdowns, and currency wars.

In that chaos, the market will impose order where governments cannot, not through design, but necessity—gravitating toward alternatives like gold or privately issued gold-backed currencies.

The Hayekian vision of a denationalized monetary system could become reality by market demand rather than academic consensus.

And it could be a situation where private actors, not governments, could help restore stability.

Fort Knox may become the flashpoint.

If the gold is revealed to be encumbered, rehypothecated, leased out or double-counted—it will confirm long-standing suspicions.

Even if the gold physically exists, if it’s already pledged as collateral or hypothecated across financial institutions, then its utility as a true reserve vanishes.

This less-discussed risk—gold being unavailable despite being present—is arguably more dangerous than outright absence.

And should a confidence shock occur, gold prices will go to the moon, the dollar will crash, and the Triffin endgame accelerates even further.

The U.S. will lose financial hegemony.

That loss might be catastrophic in the short term, but it could eventually become a long-overdue correction.

Triffin’s Dilemma may just be the market signaling “time’s up” and that the era of monetary manipulation is over.

Global financial leadership/dominance will probably just shift toward nations or systems that operate on sound money principles.

Who those nations are and what those systems might be is anyone’s guess.

And whether the U.S. adapts or resists that shift will determine its trajectory.

But one thing is clear: the trap has been sprung.

Triffin’s logic is not just theoretical anymore.

It’s clear and obvious in our trade deficits, in our monetary imbalances, and in the mounting global pivot away from USD.

If my prediction comes true, will the United States lose its military dominance?

A collapse of the fiat dollar followed by a reversion to a gold standard would pose serious challenges to U.S. military supremacy—but it wouldn’t necessarily lead to its end.

The immediate disruption and transition period would be painful.

Today’s military budget—roughly $850 billion—is sustained by deficit spending and dollar dominance.

Without the ability to inflate, the U.S. would need to fund defense through real taxation or resource-backed revenues, like gold production.

That means cuts.

We may struggle to sustain our 800+ overseas bases.

Some bases might close.

Procurement could slow.

And we may cede influence temporarily to rivals like China or Russia, who’ve been preparing for a post-dollar world through gold stockpiling and alternative financial infrastructure.

Figure 8: Gold reserves of BRICS countries (Q1 2023). Russia’s central bank holds ~2,327 tonnes of gold, China ~2,068 t (officially reported), and India ~795 t. Brazil and South Africa have relatively modest gold holdings (~130 t and 125 t respectively). Combined, BRICS central banks hold over 5,400 tonnes–more than 15% of all global official gold reserves, a share that has been rising as they accumulate gold. This is part of a broader de-dollarization push: in recent years, Russia, China, and others have increased trade settlements in non-dollar currencies and boosted gold allocations. The USD’s share of global forex reserves has slid to about 58% (down from ~71% two decades ago).

Yet the long-term picture could be more resilient.

The U.S. has the world’s most advanced economy (at $26 trillion), rich in resources, energy, and technology.

Even under a gold standard, these fundamentals remain and allow for a reconstituted defense posture.

A leaner, more efficient military—focusing on strategic deterrence and regional presence—could still retain top-tier status.

This would require strategic adaptation, we’d have to pivot to a “Fortress America” model: fewer global interventions, greater focus on homeland defense, and smarter alliances built around reciprocal exchange instead of dollar-based hegemony and aid.

Competitor nations like China or Russia may try to fill the vacuum.

Both of them have increased military spending and diversified their financial systems.

But their ability to project power globally remains limited.

This will be a massively difficult task for them.

China’s navy, for instance, is not yet a match for the U.S.’s eleven carrier strike groups.

And while their gold reserves are growing, so are their internal economic vulnerabilities.

A dollar collapse would hurt them too.

Author’s Note: China and Russia (with 2,235 and 2,332 tonnes of gold respectively as of Q4 2024) could leverage a gold-based system to challenge U.S. supremacy, especially if they weaponize new financial networks. But their militaries lag in global projection—China’s navy, for instance, isn’t yet a match for the U.S.’s 11 carrier strike groups. But many analysts believe China’s official gold holdings are vastly understated. Independent estimates suggest the People’s Bank of China may already control 5,000 tonnes or more when accounting for undisclosed purchases, off-books accumulation via state banks, and long-term strategic stockpiling—positioning China for a future monetary pivot away from the dollar. Independent analysts and intelligence sources have also speculated that Russia could hold between 4,000–5,000 tonnes in total, meaning an additional 1,500–2,500 tonnes may be unreported or strategically held outside official books—possibly within sovereign wealth vehicles, state banks, or undisclosed foreign custodians.

NATO and other alliances may strain under reduced U.S. subsidies, but cultural and technological dominance may preserve American leadership, preserving some military reach.

The U.S. may lose its status as an unchallenged hegemon—fewer overseas bases, less global policing capacity—but not necessarily its role as a dominant military force.

So, I think a total loss is unlikely unless rivals dramatically outpace U.S. advancements, which remains a decades-long proposition.

My take: A gold standard would force the U.S. military to operate within its means. That doesn’t mean decline—it could just mean reform. Reduced waste, more disciplined procurement, and prioritization of core missions might actually enhance effectiveness. It will take political will and a cultural reckoning, but leaner doesn’t have to mean weaker. As with the broader economy, the military could become more agile and resilient when anchored in reality rather than artificial liquidity.

But the question still remains: can the U.S. maintain economic growth and military supremacy on a gold standard?

The answer will come down to political will, cultural adaptation, and how willing we are to endure a period of painful restructuring.

A gold standard imposes monetary discipline—it prohibits governments from printing money at will.

While critics claim it restricts economic growth, history shows that under the classical gold standard (pre-1913), the U.S. experienced sustained, productivity-driven growth with stable prices.

Deflation was common, but not destructive—it resulted from rising productivity and falling prices, not collapsing demand.

Savings were rewarded.

Investment was disciplined.

And this makes sense, as a gold standard prevents inflation and boom/bust cycles and promotes savings and investment.

But in such a system, the U.S. would need to export competitively to earn gold inflows.

This would reward innovation, trade, and domestic productivity rather than speculation or financial engineering.

Fort Knox’s 4,580 tons of gold (worth roughly $486 billion at $3,300/oz) could be used as a war chest for emergencies, while domestic gold production—Nevada’s gold deposits are vast—could supplement reserves.

Export surpluses, particularly in energy or technology, could fund defense spending more directly.

The U.S. would need to fund its military through taxes or gold-backed revenues.

We could also seize foreign gold in extremis, which historically is not uncommon.

A reduced budget—perhaps $400–500 billion—would mean scaling back global policing in favor of strategic priorities.

However, this could lead to a leaner, more efficient defense apparatus focused on core deterrence capabilities.

Gold’s scarcity would limit artificial credit expansion, but private banks could innovate by issuing gold-backed notes—preserving liquidity while maintaining convertibility.

Prices might fall, but purchasing power would rise; wages would adjust accordingly.

Over time, a gold standard could foster sustainable, real growth—anchored in productivity and market discipline.

But then there is the issue of the national debt (now $37 trillion) which would present a significant hurdle.

It goes without saying: the national debt is a serious problem.

Without the ability to just “inflate it away”, the government would face some difficult decisions: default, restructuring, or severe fiscal tightening/tax hikes.

A short-term GDP contraction of 20–30% is possible during this deleveraging phase—which could be similar to the Great Depression—likely bringing social unrest, political backlash, and significant cuts to entitlement programs and defense.

Especially as austerity measures take hold.

Military cuts could also follow until tax bases stabilize.

Global rivals like China and Russia might exploit this transition, grabbing influence in Africa or the Middle East, but they, too, face limitations.

The U.S. retains advantages in innovation, natural resources, and military logistics that would be difficult to replicate quickly.

Nonetheless, sustaining a new monetary regime would require intense political will—an unshakable commitment to fiscal and monetary restraint that goes against decades of institutional conditioning.

It will be culturally and emotionally difficult for most Americans.

Yet, if the U.S. endures the transition, it could emerge stronger—it will be less bloated, more efficient, and anchored in sound economic fundamentals.

Growth would be slow in the beginning, but more stable.

The military would be more focused and efficient.

Strategic assets (like domestic gold mines) would become critical sources of national wealth.

Gold would replace illusion with integrity.

Alliances could be restructured around mutual economic exchange, rather than dollar dependency.

And the dollar, though diminished in global dominance, might regain trust through honesty rather than hegemony.

In the end, transitioning to a gold standard would be brutal, but not fatal.

Whether we do so by choice or by force remains to be seen.

But make no mistake: Triffin’s Dilemma is not going away.

And unless we confront its root cause (the fiat architecture itself) we will face a reckoning that no amount of central banking quant-wizardry can prevent.

Figure 9: Gold reserves by country (Q4 2024). The United States leads with over 8,100 tonnes of gold—more than double that of the next country, Germany (~3,350 t). China (~2,235 t officially) and Russia (~2,332 t) continue to aggressively accumulate, both surpassing France and Italy. India also maintains a significant reserve (~816 t), while other BRICS nations like Brazil (~130 t) and South Africa (~125 t) remain modest by comparison. As global trust in fiat weakens, many non-Western central banks are accelerating gold purchases to hedge against inflation, reduce dollar exposure, and strengthen sovereign monetary resilience.

If (big if) we went back on a gold standard, it would probably make our country and economy much leaner and meaner—growth would be real, not fake, and military power would rest on economic health, not borrowed time.

We did it before in the 19th century (with a modest but effective military) and we can definitely do it again.

But let’s face it, we live in 2025, and there is a risk that gold could put shackles on growth in a modern, dynamic economy—credit would shrink, and the U.S. might cede ground to less-constrained rivals.

Military supremacy could erode if funding lags.

But the U.S. could retain a top-tier (less global) military—think #1 or #2, not unchallenged hegemon—that’s focused on key theaters (North America, Pacific).

Economic growth would be very slow at first (5-10 years of pain), but then it would stabilize at a lower but sustainable rate, buoyed by innovation and trade.

It is plausible that the U.S. could maintain relative supremacy by leveraging its strengths—geography, resources, tech—while shedding dollar-driven overreach.

Some may call this a risky gamble.

I’d call it a healthy purge.

Final Thoughts: The Fiat Endgame

All the strands of this story—the exploding debt and interest costs, the surging inflation, the global revolt against the dollar, the desperate policy lurches, and the creeping return of gold—lead to one probable outcome: the inevitable collapse of the fiat dollar-based system.

History doesn’t whisper—it screams.

And every empire, in its twilight, must reckon with the hidden contradictions that once powered its rise.

The fiat system was never just an economic framework—it was a metaphysical wager: that man could override the natural limits of time, value, and scarcity through the machinery of decree.

Triffin’s Dilemma did not cause this flaw; it merely revealed what was always true—that a currency detached from restraint is a civilization detached from consequence.

The U.S. dollar, elevated to reserve status, became more than money.

It became myth.

But all myths, when stretched too far, collapse under the weight of their own suspension.

Now, with $37 trillion in debt and interest payments eclipsing defense, the illusion is fraying.

An economics professor once told me—half in jest, half in prophecy—that when a civilization builds its economy not upon labor or substance, but upon the ceaseless issuance of promises, it need not ask if it will fail, only when.

The hour, it seems, draws near.

Even those who long mocked the warnings—who sang paeans to leverage, to stimulus, to the divinity of debt—now murmur anxiously beneath the chorus of their own contradictions.

The edifice they raised is trembling, and still they reach for more scaffolding.

The high priests of the Keynesian order, unwilling to yield, will summon their rites once more.

They will convene new councils, offer global pacts, devise synthetic currencies, and invoke digital mechanisms to preserve the illusion of control.

They will speak of “resets” and “coordinated liquidity solutions” and “special drawing rights,” cloaking chaos and disorder in the language of management.

But this is no longer economics—it is ritual.

It is metaphysical panic disguised as policy.

As Marcus Aurelius once reminded us, “What stands in the way becomes the way.”

But these men do not stand in the way of collapse—they are the way.

For no order can endure when its foundation is not stone but smoke, not principle but power, not restraint but fiat.

To put it plainly, they seek to tame an ungovernable beast—an empire of credit fed endlessly by the power to conjure wealth from nothing.

But as Heraclitus wrote, “Much learning does not teach understanding.”

They have learned how to stimulate; they have not understood that consequence cannot be postponed forever.

And so long as any state holds the scepter of the world’s currency—while still beholden to human impulse, ambition, and fear—it will use that power to excess.

Not because it is evil, but because it is human.

The nature of man, when unconstrained, bends toward dominion until collapse reminds him of his limits.

We are witnessing that reminder now.

The spell is breaking.

The trust is fading.

The center is not holding—not because it lacks force, but because it lacks truth.

The bill for half a century of monetary alchemy has arrived—not in theory, but in hard arithmetic.

The nation borrows to pay the interest on what it already owes, and still believes growth will outrun gravity.

But this is not growth—it is metastasis.

Yet collapse is not cataclysm.

It is catharsis.

The falling away of illusion reveals the shape of reality beneath.

Just as forests burn to renew themselves, civilizations pass through fire to rediscover principle.

The destruction of the unsustainable is not a tragedy—it is a moral necessity.

The fiat order will inevitably end because it was built on a lie: that prosperity could be abstracted from value, that credit could replace character, that paper could outlast gold.

What follows next won’t be easy.

A hard money system—whether gold or its successor—demands a culture rooted in restraint.

It requires citizens who understand that price is not just a number but a signal; that debt is not just a tool but a moral hazard; that time preference is not just economic—it is spiritual.

The U.S. will survive this reckoning, but not as the same creature.

Power will shrink.

Military reach will retract.

Consumption will fall.

But so too will the false gods we erected—central banks as oracles, GDP as salvation, spending as virtue.

What will rise in their place is not guaranteed, but possible.

A leaner, sounder America.

One that produces more than it promises.

One that exports goods instead of inflation.

One that secures its borders not to dominate the world, but to defend a civilization worth preserving.

And one whose currency is once again backed by something real—not just in vaults, but in virtue.

This, perhaps, is the deeper lesson the ancient masters have long understood: that money is not merely a medium of exchange, but a mirror of civilization’s soul.

Sound money is not a policy—it is a principle.

A discipline.

A covenant between present and future.

And when that covenant is broken, the reckoning is not only economic—it is civilizational.

Triffin’s Dilemma was not a glitch in the matrix.

It was the signal flare.

It warned us, decades ago, that a global reserve currency unmoored from discipline would eventually collapse under the weight of its own contradictions.

We ignored it.

We papered it over.

We rationalized it with graphs and fancy words.

But reality cannot be indefinitely delayed.

The Keynesians will write their memos.

The technocrats will run their simulations.

But none of it will matter, because the deeper truth is this: you cannot centrally plan faith.

You cannot print trust.

You cannot algorithm your way around consequence.

And so, the fiat era ends—not with a bang, but with a quiet vote of no confidence from the markets, from the people, from the mirror of nature itself.

It will mark the end of empire by ledger.

But it may be the beginning of something better—if we’re humble enough to return to first principles, and wise enough to listen to what history, and nature, have always said:

You cannot cheat the laws of value.

And in the end, reality always wins.

If you like The Unconquered Mind, sign up for our email list and we’ll send you new posts when they come out.

If you liked this post, these are for you too:

America’s Hidden Economic Civil War

Game Theory for Applied Degenerates